Nicéphore Niépce

« This is but an imperfect trial, but with much patience and work we can do great things. »

Nicéphore Niépce, the inventor of photography

With his invention, Nicéphore Niépce dispensed not only with the status of the reproduced work, the image, but also the subject, the simple subject of all man’s creations. Heliography changed everything and since its invention, nothing has ever been the same. The order of things was forever transformed.

What happened after 1816 in the history of representation was nothing but the deposing of the hierarchy of genres. Heliography brought the nature of things back to their measure and at the same time upset them totally: the new status of the object dismissed in favour of multiplication and dissemination. But paradoxically, there would no longer be any object without interest. From this point on, everything became clues, proof, and fiction. The invention freed us from the real.

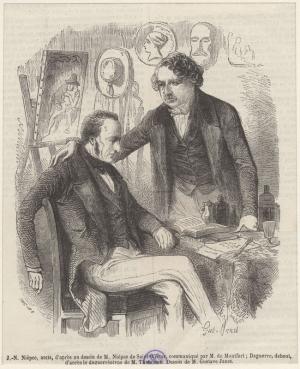

The history of photography has only recently begun to recognise the decisive contribution made by Nicéphore Niépce. In a history of photography that is always riddled with contradictory interests, the fact that he was the first to clearly outline the general principles of photography, meaning « fixing images of objects through the use of light », did not ensure his status as inventor. The sad London episode (1827), his premature death (1833), the official title given to the invention, « incorrectly called » daguerreotype (1839) and the English claim for the discovery made by the Englishman W.H. Fox Talbot (1839-1840), all unfortunately combined to turn history away from the path of equity and gratitude. Nevertheless, Nicéphore Niépce’s work takes an essential place in the history of photography through its anteriority and effectiveness and without him Daguerre would never have been in a position to present his own work to Arago as it was largely consecutive and dependent on their partnership contract (1829-1833).

Nicéphore Niépce’s letters and writings form a space where his proposals spurt out and organise themselves. The thinking might appear confused at times as everything comes together and is transformed in the associated field that Nicéphore Niépce referred to as heliography. The reconstitution of events and the discontinued mode of expression do not reveal the incoherence of his work, on the contrary they reveal how strongly rooted it was in the complexity of the real. The invention of photography is unique in its mode of announcements and statements. The numerous letters in the museum’s possession, the way they emerged, the law of coexistence with other statements, like the treatise on heliography, elaborate the principles that form the basis of the evidence of photography. Nicéphore Niépce was the first to be fascinated by what he glimpsed and succeeded in doing.

The resulting literature swings from the humility of manual work to a fascination for magic. Nicéphore Niépce’s letters validate, legitimise but above all give the object meaning. From one letter to the next, we follow the process, with his questions and doubts, a discourse that interrogates the practice. But above all, the epistolary exchanges prove his conviction, belief and the solid basis for his invention.

Heliographs on metal are not all of the same type. Nicéphore Niépce discovered the virtues of Bitumen of Judea when exposed to light. Based on this principle that owes much to engraving, he developed two potential options, the fixing of the « viewpoint » in the camera obscura

and the reproduction of the engravings.

Certain metallic plates like "La sainte Famille", with their clean, deep cuts, and network of precise chops, were designed to be reproductive models.

Others, such as the plate commonly known as "le joueur", have a less precise drawing that permits no prints after inking. So it must be considered as a simple reproduction and not as a model. In addition, they appeared at a time when Nicéphore Niépce (March 1827), was experiencing one failure after another with his prints from engraved plates.

During the summer of the same year, a crucial year for the invention, Nicéphore Niépce took another path using Bitumen of Judea and obtained images directly from the camera obscura . The photograph « Le point de vue du Gras » is the first example of a finished, fixed image on a photosensitive surface.

In the whole collection of engraved plates, one late image (1828), the plate entitled "couple grec" has a particular place in Niépce’s production. The un-engraved image, - by the way, it holds very little interest -, seems to be placed on the metallic surface. Brass replaced tin and was covered in a thin layer of silver so the image appears positive, the result of inverting the iodine, two principles that precede the daguerreotype by ten years.

So this is the heritage of Nicéphore Niépce, a wide range of methods that go from taking shots using a camera obscura to the little known photogravure process. There is no longer any doubt as to the technical success and effectiveness of the work of Nicéphore Niépce. But it is our job to measure the effect this founding act had in real terms.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

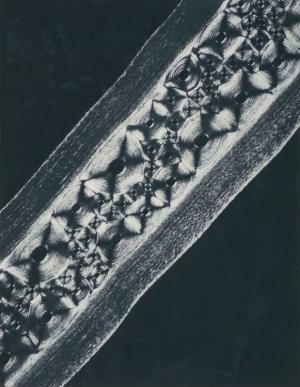

In the mechanisation of the image, the 19th century saw a means by which to improve the effectiveness of representation and in doing so, provide an ultimate explanation for everything. The camera was a way to see more and better: microscopic, aerial, satellite, radiographic and 3D photography… Man thus added to his visual capacities. He understood the universe better and was in a position to wield more power over it.

The camera gained its autonomy and engaged in a permanent race for progress. Today, it can switch itself on with a simple smile or movement. Technology produces the image, taking the need to master a process which had become too complex out of our hands.

Masters of time?

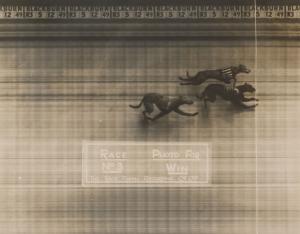

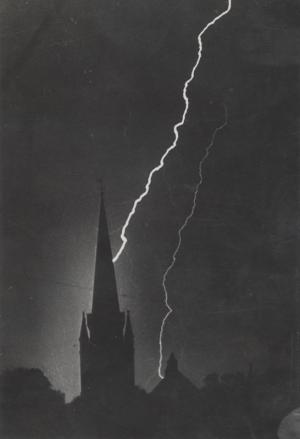

The quest for instantaneousness in pictures has been a constant since the invention of photography. Technical progress, the emergence of gelatine-bromide silver prints meant the time between taking the photo and the resulting photographic image got shorter and shorter.

The elimination of the time span between the click of the camera and the actual photo has been the quasi-utopian objective since the start and it was finally attained with digital technology. Instantly sending the image through space was the other clear aim since the invention of the belinographer and is today possible through the internet and the smartphone.

Photography thus fulfils the universal fantasy of mastering time and space, and through it, the spreading of universal knowledge. The simultaneousness of the event, its capture, broadcast and reception is now the norm. This immediacy is an illusion. Confronted as we are with a continuous flow of « informative » images, we experience events live from all over the world without necessarily understanding them.

Far from the objectivity it was first claimed to have, photography is the perfect instrument for creating a world that is parallel with reality. When used to serve the ego, it makes it possible to display oneself, to attenuate one’s uglier physical traits, to reinvent one’s life. Once framed, inserted in an album or posted on an internet profile, it reflects what we are prepared to show, what we think looks good. The downside of this ideal is the self-censorship that follows, and in the end the uniform nature of the images, the repetition of stereotypes we thought we were escaping from.

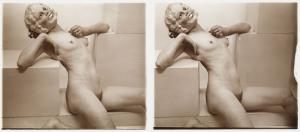

Beyond its capacity for modifying the presentation of reality, photography also has the power to influence our senses and our desires: erotic images, crime scenes… It becomes the privileged influence of our fantasies, prepared to fulfil our passions, feeding universal voyeurism.

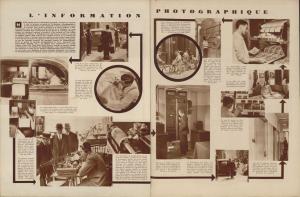

A misleading encyclopaedia

From the beginning, photography was seen as the ideal tool for the worldwide spread of knowledge. The facility in reproducing this mechanical image led people to believe that photographing everything would lead to a global and exhaustive knowledge. But the accumulation of images has had no effect. It shows us things without providing the keys to understanding. Sometimes, for certain photos that have become iconic, it can be limited to idolatry, to the passionate, leaving any possibility of a critical thought as to the subject by the wayside. This utopia of access for all to universal knowledge, despite the mass spread of images from the 19th century onwards and even more with the internet today, remains conditioned on the economic, intellectual and social capacity of each individual.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français