Stéphane Couturier

Alger, Climat de France

10 15 2016 ... 01 15 2017

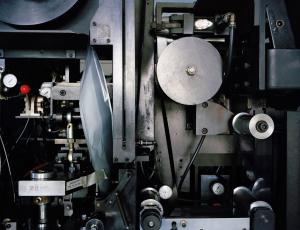

Stéphane Couturier examines urban development and the metamorphosis of buildings. With elegance, the photographer manages to reveal the “guts of the city”; his photos, whether they are taken in Paris, Berlin, Havana or Seoul, are the result of the inextricable overlapping of a hyper-realistic rendering and the dissolution of form. His project “Climat de France” (French climate) came to be in 2011 and is based around Fernand Pouillon, a figure of fifties architecture who was one of the biggest builders in the reconstruction that occurred after the Second World War. Using photography and video, Stéphane Couturier dissects Algiers’ biggest group of tower blocks, built during the Algerian war, the location of much confrontation between the GIA (Armed Islamic Group) and the authorities and now a hotbed for all types of trafficking.

The city is a collection of sequences, of course, but it remains a block. Building by building, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, portrait by portrait, Alger seems indivisible. The fragments correspond perfectly to the idea of the city. We know, we’ve said it often enough, the idea and the object cannot coincide. Nevertheless, here, Stéphane Couturier comes close to the “truth”. He does not convoke our senses but he makes us see the matter. By systematically depicting images in series, he detaches himself from a solely ‘matièrist’ depiction. His photography aims to give an account of this event through the infinite number of circumstances that accompany it.

The photographer provides us with glimpses of the living, but does so not by convoking chance. The idea of the fragmented band joins them, or, connects them to a form of thought that gives them meaning. The precise representation of the properties of that which is exposed incites the viewer to comment. The photographic method is implacable.

Is truth, then, not to be found in the precision of these lines? The knowledge of things is nevertheless inseparable from these suspended objects, running along interminable facades. That which is fleeting, people’s everyday stories, make light of the monument and its essence. Time is the main issue in this photography; each image comes with its own layers of history. Long term time is depicted beside ever-changing current events. Sheets and clothes dry and satellite dishes signal modernity. Out of time and in the moment, photography proves that nothing comes before anything else.

[…]

We see how Stéphane Couturier constitutes his photographic universe. As a viewer, believing we are contemplating extensive documentation on architecture or simply compiling an insensitive inventory, we contemplate our own relationship with order and disorder. All of these images, with their subtly repetitive construction, echo our anxieties and our desires. Photography, in olden times, liked to define good and evil. Here, the approach is more like describing the imperative of things and its antidote, the fluid. In these photographs, we never come up against the solid. Life is avoidance and withdrawal.

François Cheval

Climat de France, « an architecture without disdain »

Fernand Pouillon was an architect of Mediterranean sensibilities known for his designs of high-quality, low-cost housing developments with a great many units. The mayor of Algiers commissioned him in the nineteen-fifties to design three such projects, including the Climat de France complex. These developments were built for the purpose of relocating the Muslim population that was living in cramp conditions in shantytowns, thereby contributing to reducing social tensions and reasserting the authority of Metropolitan France.

Overlooking the working class district of Bab el-Oued and the old city, and facing the sea, Climat de France was the biggest of these developments, offering nearly 5,000 housing units. (…) The main building is structured around a rectangular plaza, 233 x 38 meters long. White stone columns line the interior building fronts, giving them a classical look. Pouillon wrote:” I’m sure that this architecture is without disdain. Maybe for the first time in the modern era we have settled people in a monument. And these people who were the poorest of poor Algeria understood this. They were the ones who named it “the 200 Columns”.

Today, Climat de France is an overpopulated housing development, some of which is dilapidated and unfit for habitation. The cellars have been converted into rooms and the rooftop of the 200 Columns building – initially designed specifically with the housework and social life of the women in mind – has been turned into a shantytown. The plaza has been dubbed La Colombie (Columbia) for all the trafficking and dealing that goes on there and the police don’t enter the project anymore. But the stone architecture has nonetheless withstood these overpopulated conditions much better than concrete would have done.

Etienne Hatt

Journalist, on the editorial staff of artpress

Publication :

Stéphane Couturier

Alger – Climat de France

Texts / François Cheval, Etienne Hatt

Editor : Arnaud Bizalion

Marseille, 2014

23x32 cm

76 page

ISBN : 978-2-36980-023-1

30€

Stéphane Couturier

Texts François Cheval, Matthieu Poirier

Editor : Xavier Barral

Paris, 2016

24x30 cm

308 page

ISBN : 978-2-36511-111-9

39€

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Lamia Joreige is an artist and filmmaker who lives and works in Beirut. She uses archive material and fictional elements to examine the relationship between individual stories and collective history and to explore the representations of the Lebanese wars and their aftermath in Beirut, a city at the center of her imagery. In the exhibition “And the living is easy – Variations on a film,” Lamia Joreige presents a three-part installation based on the feature film she made in Beirut in 2014. In this film, through the depiction of the daily life of five characters, Lamia Joreige provides us with a portrait of her native city that lies within the beauty of the images, the apparent sweetness of life, and the anguish associated with the political instability in the Middle East.

The political, social, and urban changes that have occurred in Beirut from the nineties to the present day, have transformed the city and its way of life. For the past ten years, Beirut has been a city held in abeyance, ‘frozen’ in a present that prevents us from projecting ourselves into the future, in expectation of a resolution to not only the country’s conflicts but those of the entire region. This state of suspension is at the heart of my feature film And the living is easy, which I directed in 2014 and which will be screened daily during the exhibition.

What are the questions that arise when one shifts from the filmic space to the exhibition space? What happens in the thought process guiding a piece from its origins to its creation; and, inversely, after it is realized, what happens when we undo it, rethink it, and reinvent it?

The installation And the living is easy – Variations on a film interrogates the fabrication of my feature film And the living is easy (2014) and the possible forms it creates. It is divided into three parts, or Scores (Partitions , in French)—the Screenplay , the Soundtrack , and the Cartography of the film —that reconfigure the material, space, and length of the film in the exhibition space.

There never really was a script for And the living is easy . The shooting took place in 2011 and was entirely based on improvisations. The scenes were inspired by places in the city and by the desires of the characters, who, for the most part, were not professional actors and mainly played their own roles.

Thus, Score l , the image-text is a document written after the work whose entire material it traces, from the shooting to its realization: it encompasses the shooting and the production—including the scenes in the same order they were edited—the corresponding takes that were dropped during the editing, as well as the scenes that were shot but discarded in the final cut.

The typescript, presented as a frieze of more than 15 meters, underscores the creative process while allowing for speculation and suggesting multiple readings.

Score II , the soundtrack, is a sound installation in collaboration with Charbel Haber, set up in the exhibition space. This work interrogates the notion of a soundtrack in cinema by deconstructing that of my own film and recomposing it in another form, another tonality, and within a different spatial configuration. The challenge was to use no external instrument, whether analog or electronic, and to work only on the soundtrack of the film, without adding anything, yet working on the speed, reverberation, spectrum, and texture of the sounds.

Score III reverts to the historical principle of the frieze in order to reflect on what has happened in Beirut between the time in which the film was shot and today, on a sociological, political, historical, human, and geographical level; to examine what has happened between the two periods. The film becomes a prism through which I observe this period, and its geography becomes the main thread of a collage made of photographs, videos, texts, personal notes, newspaper articles, where the real and the imaginary blend together to tell stories—quotidian events, historical movements, or imagined narratives—proposing us a non-linear reading. Here, as in my previous work, the question of history and its possible narratives is central.

As a prelude to the main installation, Beirut 1001 views , the second chapter of Beirut, Autopsy of a city (2010), will be presented in the exhibition. Evoking a palimpsest, this video based on photographs from various periods, brings together different temporal elements that perpetually fluctuate between absorption, disappearance, and reconfiguration.

Lamia Joreige

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

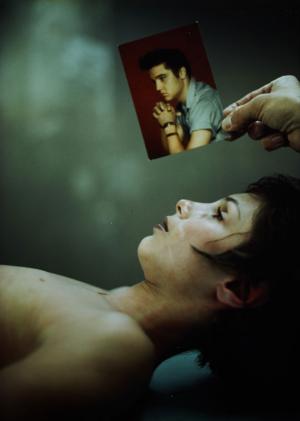

Famed for his monumental brushed bichromate portraits, Yan-Pei Ming attempts through them to conceive the universal portrait, without making resemblance a focal point. He is a compulsive and persevering artist, working independently of the ups and downs of ephemeral artistic trends, creating series of portraits, painted from live models, memory or from photographs. It is the latter that interests the Nicéphore Niépce: Ming has been invited to consult the collections and to conceive, like a performance piece, a unique and unprecedented exhibition based on iconic or anonymous iconic photographs from the museum’s collections.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

The expert eye

Contemporary photography

06 18 ... 09 18 2016

In December 2016, François Cheval will step down from his job as director of the musée Nicéphore Niépce. It is an opportunity to review twenty five years of an unprecedented acquisitions policy in terms of contemporary photography.

The museum could never be referred to as a place for keeping old works of art, pieces from those with “established” pedigrees. On the contrary, it has always taken its role in supporting creation very seriously. It has hosted artist residencies, constituted bodies of work that provide a comprehensive overview of the careers of many artists, it has produced prints in tandem with the photographers themselves, it has set up artistic projects in the town of Chalon, and these choices opened the collections up to a reflection on the world and the medium through the expert eye of the artist.

This exhibition was put together with support from :

Olympus France, BMW France, Canson, HSBC, the Ministry of Culture and Communication – / DRAC Bourgogne Franche-Comté and the Friends of the Nicéphore Niépce museum.

In the original model of the musée Nicéphore Niépce, founded by Paul Jay in 1974, the photographer and the artist were one and the same. The founder surrounded himself with a range of characters such as Philippe Néagu, André Jammes, Jean-Pierre Sudre, etc, and the period gave rise to a certain affirmation of photography as an art form, nostalgic for know-how and a search for the truth of the medium as an individual creative space. Jean-Claude Lemagny’s declaration of love was taken up by Paul Jay: “To love photography carnally. The expression may seem bizarre but I simply wish to point out that all true love is of the flesh

”.

Photography was first and foremost about what could be felt. It was talked of as of a loved one, describing its tactile qualities. “Skin”, “flesh” and “matter”, such was the truth of a humble photography, far from the market, from contemporary art and its concepts. The facility of the big format was to be mistrusted, colour suspected for its vulgarity. In short, the only photographers invited to show in the museum were those who occupied the moral high ground. The contemporary photographer, a veritable demigod, an “auteur” in the full sense of the term, was almost considered to be an alchemist, an apprentice sorcerer.

Since 1996, the figure of the all-powerful photographer has been replaced by the photographer seized by doubt and uncertainty! Twenty years of contemporary acquisitions have called the medium invented by Nicéphore Niépce definitively into question. The issue became more than just introducing a new aesthetic, each image and each series spread doubt about the preconceived notions about the photographic act. It was important to avoid reducing things to the inner circles of the photographic milieu so the collection chose to provide an alternative to the “vulgar” images of the world. The contemporary collection is a militant act, embodying a fierce intention to stand up to entertainment, to a society hooked on showbiz. It shows a series of new perspectives from photography professionals, well-versed in the ruses of the medium, not by sacralised “auteurs”. To this end, the choice to only acquire complete series, to produce them often, and to create loyal relationships over time provides an overview of both the crisis in photography and its possible regeneration.

The roles we give to all of those we invite or summon are multiple and complex. They are asked, this time without humility, to rebuild the photographic object in its entirety. To do so, they are required to participate with gusto in the destruction of a tottering old edifice that is crumbling under attacks from modern media and social networks. Everything is up for grabs. All of the criteria imposed from the outside are there to be undermined; the auteur and the concept of the photographic work, that undefined category of “intention”, the arbitrary “periodisations” and the “history” of photography.

The musée Nicéphore Niépce is no longer obsessed by rarity and the unique print. Thanks to the museum’s technical facilities [ production laboratory, residencies…], it has managed to propose a new form of relationship with the photographer. The term “auteur” has been replaced the term “expert”, a term we prefer, that defines a person with the technical and cultural know-how needed to question the anthropological relationship between modern man, the camera and the world at large. The acquisition policy was constructed in a permanent state of polemic between the provincial institution and the photographer. The “subjects” surfaced after fights and debates. They took shape in opposition to the art market and the institutionalisation of art. They emerged thanks to the economic situation and the cultural crisis in photography. We once spoke of “necessary” purchases when the notion of art, which here is useless, disappeared in favour of critical but always joyful narratives. Contemporary photography can today only take credit from its attempts to bear witness not to the state of the world, but to the relationship we maintain with the autocratic image that blends with the new merchandise. It brings before us the object of predation, it exhibits a clear tendency to reduce head size, a permanent temptation to be a totalitarian and futile object, an object of social control and pure satisfaction.

It stands up to the medium’s supposed capacity and legitimacy to reproduce the real, to its objectivity.

What the eye of the expert has brought to the musée Nicéphore Niépce and to its visitors is the demonstration of a photography without any real consequences on the world, but a photography that gave the impression of a new found freedom. Liberated from narcissism, decoration and artiness, contemporary photography was set free to play with the machine and its potentialities.

François Cheval

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

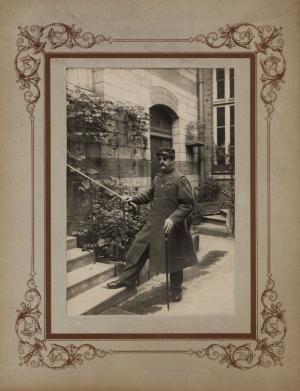

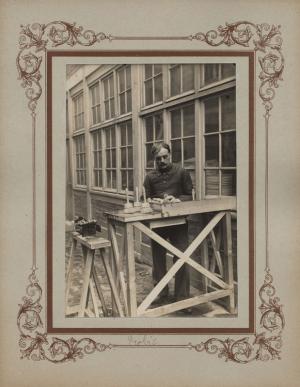

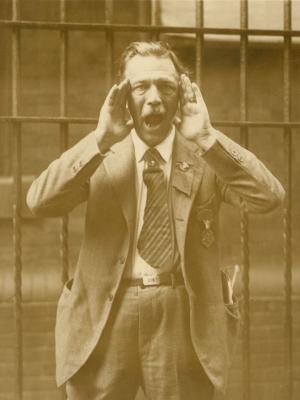

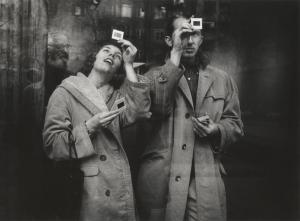

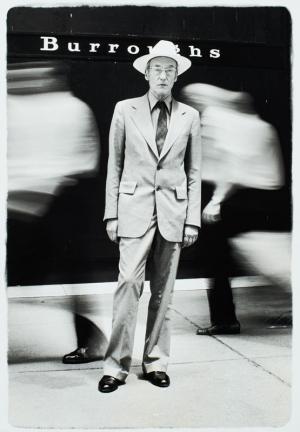

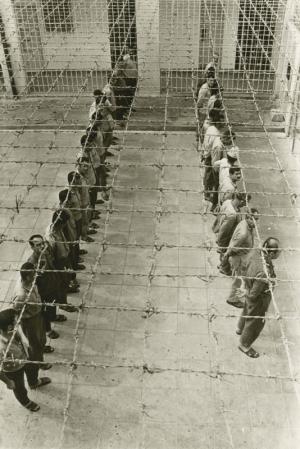

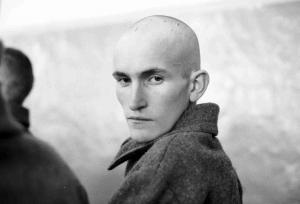

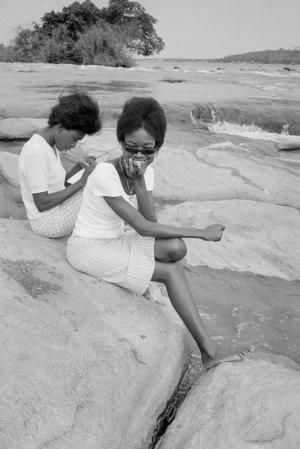

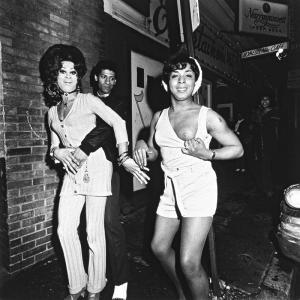

Léon Herschtritt [ b. 1936] was the youngest photographer ever to be awarded the prix Niépce in 1960 thanks to the work he did during his military service in Algeria. As a true humanist, he was quick to diversify his subjects, developing a particular sensibility for street scenes, young people in the sixties and their progressive emancipation, social movements, the gypsy populations…

Using the photographer’s personal archive and at times developing photographs from negatives that have not yet been used, this exhibition is based around eighty photographs that provide the viewer with an overview of Léon Herschtritt’s work in the sixties. In some way, his work bears witness to the end of an era.

This exhibition is made possible by the support of :

Canson, the Ministry of Culture / DRAC Bourgogne Franche-Comté and the Friends of the Nicéphore Niépce museum.

Léon Herschtritt’s work is a trial for the critic. The series emerge without having to be decoded. They are obvious. A prostitute shimmies, a soldier puffs out his chest, Parisian couples smooch on benches. Today, photographers are lauded for originality. Edginess is the rule and this is not a bad thing as conformism in photography lacks nuance.

However, we must not forget one of the medium’s essential qualities, to show things again and again and to comfort the memory. In this show, we retrace our steps. We take pleasure in going down well-worn paths. Today, who dares to paint the portrait of a country or a profession, who dares to feature lightness, joy, sadness and despair? Mood photography, is that in fact the simple definition of the work of Léon Herschtritt? Things aren’t that simple. It is a trial for the critic! As, given the agitation of our own constantly shifting present, we are not in a position to judge the era.

We lay claim to freedom of perception and nevertheless, we can’t help characterising this photography as melancholic. However, if we could, just for a moment, set aside that which is anecdotal and out of date, we would be forced to admit that the times were in upheaval. Behind the futile appearances, behind the equivocation, we can detect the premise of a dark future, our present. In the sixties, a time considered to have been “glorious”, nations were emerging, young people were preparing for rebellion, strikes were widespread and the world was splitting into two camps. In what seems to be an endless parade of shallow, carefree moments of grace, the photographer captures a real sense of movement, of both things and people. Today, we are aware of what nations were going through, from the fall of colonial empires to the culture crisis.

The not-so-humble photographer bears witness to the fragility of society and the futility of photography. It would be incorrect to take Léon Herschtritt for a photographer with a critical eye. Nevertheless, when he focuses on a subject, nothing is direct. His vision moves over that which is, to all intents and purposes, relatively incidental. Photography is not to be found in the answers it provides, and offers even less in terms of solutions, but it does question its participants, the actors or extras in this theatre.

Photography has never been as “devious” as to take us down a series of wrong paths and we would be mistaken to understand this way of diverting the issue as a “humanist” artifice. Léon Herschtritt gets away from the tragic, from excess and eye-catching contrasts so as to impose his lucid, clever, non-acrimonious photography. He finds the right level of expression of his work in a slightly nostalgic if somewhat sharp approach, structured around the way things and men work. The photographer’s main aim is to contain each image within a narrative that owes nothing to the great photographic works he knows and appreciates. He exercises the profession of photographer-reporter without shame, confident in the rough quality of the tool. The resources of the machine itself are enough for him to express that which lies beneath.

So it goes, the work of Léon Herschtritt, it lives without fits and starts, almost underground. In describing it one often is often misled. One could be led to think it was declining. Then, it is exhumed. It arouses more than curiosity. And, it is quite possible that one day it will awaken the uneasiness that brought it into being.

François Cheval

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

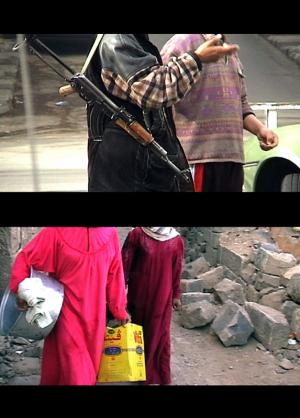

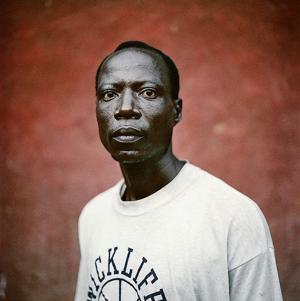

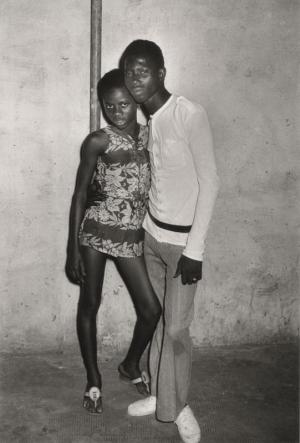

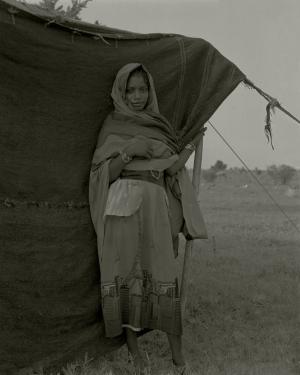

Claude Iverné has an uncommon way of working as a photographer. He refuses to be seen, despite the fact that it is now considered the norm for reportage to be in the first person. This is why this remains a resolutely “purist” vision of documentary photography, with no room for egocentrism. Reality is dark so the photographer remains in the dark.

By making the processes of “ethnographic” photography his own, Claude Iverné also adopted its principles. For him, the role given to the photographer-reporter is not enough, nor is the role of simple spokesperson for “suffering” populations. He takes on their codes and their logic. He is in no way looking for a “natural state”. We would be mistaken to think of him hunting for the “truth” of a people, on the contrary, his approach is a series of mysteries.

The reasoning that produces this photography is far from explanatory. We get close to things, through their most concrete aspect. The spirit of the series brings us face to face with the matrices and their versions. His result becomes ours: a question without answers.

Our era marks a certain defiance toward reportage photography. Is there an alternative to images whose origins are only rarely certified? Faced with the “uselessness”, or more to the point, the ineffectiveness of photography as a witness, is a regeneration of the language of documentary possible? It would appear that by inverting the order of time, by shifting away from the urgency, we can approach new territories for understanding the world.

While there is a tradition that ensures the pre-eminence of black and white photography over other modern media, it is without contest due to the virtue of silence. The fixed, monochrome image retains the quality of economy unlike the permanent flow of information, whatever its nature. Restraint, that should be the rule everywhere, is, at the very least, the murmur of reality in the situations presented by Claude Iverné…

By banishing seduction and emotion while founding an aesthetic, the photographer includes in the latter the critical possibility of the visible and its perception. The expectations of the viewer, the pre-vision of a humanitarian image being our era’s “exoticism”, are up against the only possible way to read the real, its transfiguration. The question of the restitution of the real does not necessarily require the requisition of impressions. Without logos, the operator has an effective tool at his or her disposal, a desire for distancing.

The will to “faithfully” reproduce the world is paired with a certain resolution to go beyond current affairs and with a brusque disregard for emotion. The observation of Sudanese society according to a strict procedure, amplifies the impression of a gap between the treatment of the subject and its urgency. The images do not appear as “unicas”, singular objects, but appear to us as simple elements of a complex game. Photography is a “Krieg spiel”.

Exteriority validates the commentary. The blindness of the photographer is as that of Tiresias. Faced with disaster, the operator resists by mastering the technology. The submission of the camera is the beginning of renunciation. Otherness begins where the technical aspect is subjected. Claude Iverné speaks Arab. This perhaps leads to an appreciation for the real that owes nothing to the fake poetry of travel. What is missing from these series is romanticism, they are in no way symbolic or disenchanted, nor are they crippled by Rimbaud syndrome. The practice of photography, like learning a language, is a permanent initiation to difficulty, better even, to impossibility.

Ever since we’ve known that things are bad in Africa, the continent has been left without the promise of a future. It is what it is. This is what Claude Iverné has to say. Unlike a “traditional” photographer, imbued with moral consideration, he does not raise the document to the level of testimony. And, amused by the messianic role that he has been assigned, he only sees his different interventions through a disassociation from traditional reportage. He sets up the idea that this journey reveals nothing by itself. It is a decoy, obviously, but not the most deceiving, here and now.

The images imbued with a strange tone into which the series meld, do not provoke fantasy and even less the desire to leave. The narrative focuses on the biotope’s fault lines and contradictions. The point of this work is to break with the different models of photographic narrative. Obviously, we don’t find a modernisation of the myth (at the source of the Nile!) any more than we find personal serenity. Darfur is similar in many aspects to the banality of other regions.

The lack of differentiation in the material does not lead the photographer into the abstract. The image arranges the nuance. If it refutes contrast, meaning the simplistic organisation of a split between good and evil, it is to all the better to undo the drama. The description of reality records only unqualifiable moments as they are universal. “

The way in which men

produce their means of subsistence depends first of all on the nature of the actual

means

of subsistence they find in existence and have to rep

roduce. This mode of production

must not be considered simply as being the production o

f the physical existence of the

individuals. Rather it is a definite form of activity of these individuals, a definite form of expressing their life, a definite mode of life on their part. As individuals express their life, so they are. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production, both with

what they

produce and with how they produce. The nature of individuals thus depends on the material conditions determining their production

.”

Karl Marx. F. Engels. 1845. The German Ideology.

The wish to confront the world through photography, a relationship mediated by a camera, only makes sense if the relationship is shared. Here it takes on different forms, from a published document to a photo hanging on a wall. What is important in the restitution is the situation. Whatever this means for the photographer, if the shot forms the raw material, the clue that is necessary for all ulterior commentary, then the commentary is based on the initial intention. The final event is at the heart of the photographic journey.

François Cheval

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

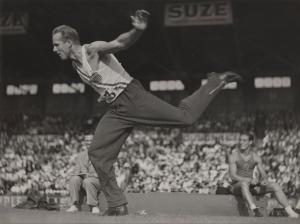

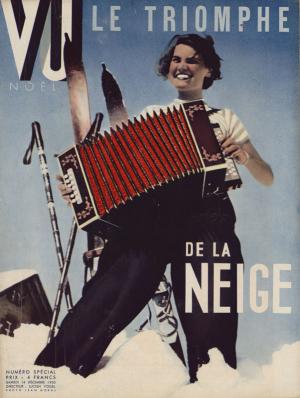

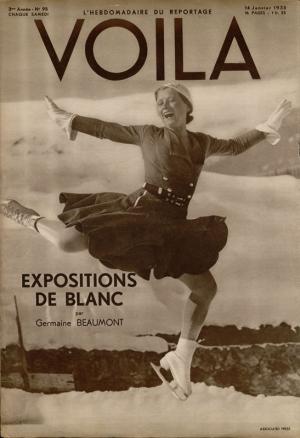

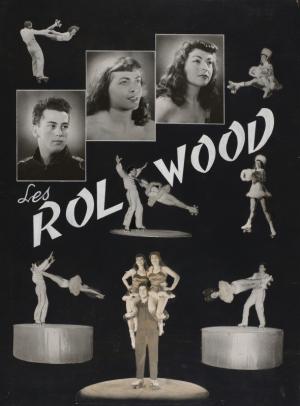

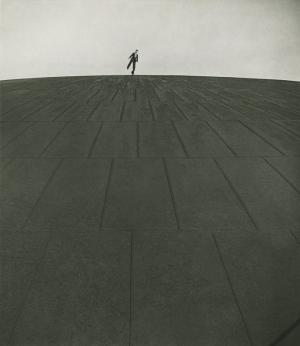

The thrill of movement

Sport and photography

02 13 ... 05 22 2016

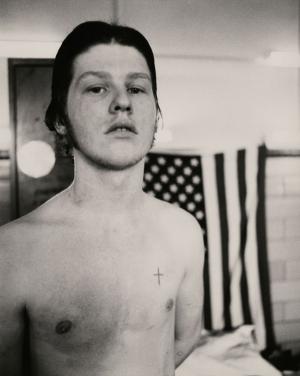

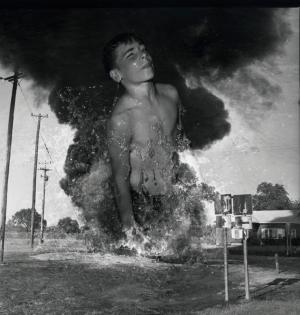

It is misleading to take multiple representations of the body to be an offshoot of the photographic portrait. The portrait is a tentative approach at a psychological profile. The photographed body captured directly is a manifesto. The body needs only itself to put on a display. The portrait relies on the decor, an accumulation of attributes to bolster its meaning. Thus we go from an image laden down with objects and signs, to a stark image that focuses on the consequences of effort. The quest for movement that adorned the first photographic magazines shifted to make way for a sculptural aesthetic. While, to begin with, Marey and Muybridge were useful in the understanding of movement, photography in the thirties took on the traits of the ancient arts of sculpture and the nude. We would be mistaken to see this evolution as a passage from the eugenics of physical education to a recognition of the intimate. The social and collective practice of sport dispenses with nudity’s air of indecency. The naked body loses all its erotic meaning in favour of a societal ideal.

Gymnastics was initially a social practice reserved for the “elite”. It was part and parcel of the art of self-representation. Through the conspicuous exhibition of a straight-backed body, photography celebrated a way of life by rejecting the concept of “letting oneself go” and giving in to temptation and pleasure. The new “aristocracy” of the inter-war years, through the quest for the perfect movement, saw sport as belonging to a certain modernity that didn’t involve individualism, taking their inspiration from eugenics. Performance took over from well-being and life in the fresh air was nothing but a continuation of the prowess seen and admired in magazines.

A wide range of new magazines displayed the geometry of the body in their centre-folds. Physical education and health manuals were reduced to restricted circles. The idea was no longer to manufacture bodies that were ready to fight the barbarian (the German neighbour) and asceticism was not behind the new idea of the body. Sport photography was evidence of the power and wealth of a nation. Parallels with this new sensibility, the shift from a lifestyle to the exaltation of sporting exploits can be found in the dynamic of the press of the time and, in particular, with the development of reproduction techniques. The press latched on to the photogenic nature of the sporting body that was in fact represented as a demi-God, the heir to the Homeric hero, taken by surprise in close-up.

Sport and photography came together to define modernity. They shared the idea of a moment shared and its instantaneous nature. Photography went way beyond film as it was precise and close to the action. It transposed a moment the very nature of which was ephemeral. What in fact the magazines from the thirties invented was the transfiguration of a simple act into an epic poem. The mechanical image, supported by praise-filled text, transcended the event to turn it into a veritable collective phenomenon.

As early as 1919, those who were referred to as the “preparatists” wished to contribute to the reconstruction of France. In 1918, the power and good health of one people overcame the power and good health of another. Nevertheless, the crux now became the exemplarity of the winner and not just principle and virtue. The spectacular character of photography now required more than just bodies gambolling in picturesque landscapes. It needed the spectacular theatricality of the stadium so that the body could express its dramatic qualities and provide support for the myth. Photography thus became an essential component of a totalitarian ideology.

The value thus accorded to the body required the de-realisation of the subject, the other materiality of the corporal substance. Effort was a symbolic charge. The image of the champion’s anatomy was raised to the level of the sacred. As an unperishable envelope, it integrated into the long history of the West. However, the body of the “other” was thus dehumanised, ready to be sacrificed. The magazines of the intelligentsia and in particular “Vu” did not hesitate to associate the used-up body of the working man with the century of industrialisation. The body no longer belonged to individuals. The body of photographic modernity became a social construction, a piece of fiction.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

In all Directions

06 13 2015 ... 01 03 2016

Understanding the photographic. More than ever, the musée Nicéphore Niépce continues to affirm its position as an all-purpose photography museum. It promotes photography as a whole that, since Niépce’s initial foray, cannot be reduced to just art and technique, or to the blend of the two disciplines. The choices are partial, this is not an exhaustive show, but one that emphasises the educational link between the photographic object and the spectator.

“Tous azimuts” (In all directions) presents recent and heretofore unseen acquisitions. The pieces include both purchases and donations and are a timely reminder of the museum’s vocation to assemble, conserve and show photography.

As a multi-faceted, ever-changing object, photography can be shown on walls, in books and magazines. It is freely exposed in family albums. To perceive photography in its coherent state and attempt to rebuild a photographic archive in its totality means going back to the way it links to our obsessions, our desires and our perversities; at the risk of putting the staggering panorama of humanity’s fascination for the medium on display.

An advertising object

From the end of the 19th century, the demonstration power of the photography made of it an advertising object. But it was especially between the two wars that the photography was able to exceed the former advertisement based on text and drawing. Praising a product’s advantages, a brand or a commercial chain, it displayed on every kind of medium: poster, catalog, calendar, letter holder… The image’s impact is instantaneous. This one is supposed to prove the veracity of the message. At this time, the advertising image got back and was inspired by the avant-garde’s plastic experiments: photomontages, use of typography and color. Besides, it’s not harmless to note that the greatest photographers worked for advertising market.

Photography in wartime

Photography in wartime is a multi-faceted genre. Its principal characteristic since 1914 has been, above all, the way it has been controlled to be used in the press as propaganda. Images were often retouched, scenes reconstituted after the fact. Photography became a weapon of persuasion to reassure the population (showing nothing) and to terrorise the enemy (showing them decimated). Totalitarian regimes added the cult of leadership to the mix by flooding conquered territories with thousands of solemn and intimating portraits. Then there were the souvenir photographs taken by soldiers that were, at times, very supervised.

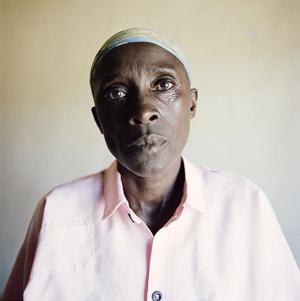

The mission of photo-reportage from the thirties onwards was to show what was going on in the wings, that which was hidden, to incarnate the conscience, to contribute to changing things – in vain. The representation of horror has never prevented it from existing. This horror can only be evoked through metaphor, transposition, like the way Laurence Leblanc takes close-up shots in modelling clay of the characters in a Rithy Panh film in the Khmer genocide. Or how Alexis Cordesse gathered testimonies from ex torturers from the Rwandan genocide that he put together with their intentionally banal portraits. The image does not work as immediate proof, it is instead a testimonial. The effect is no less forceful, it is amplified.

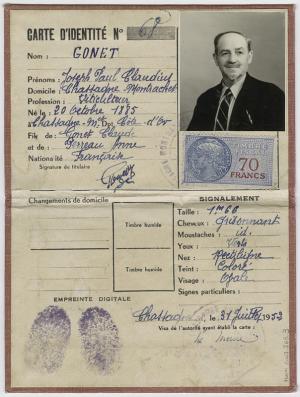

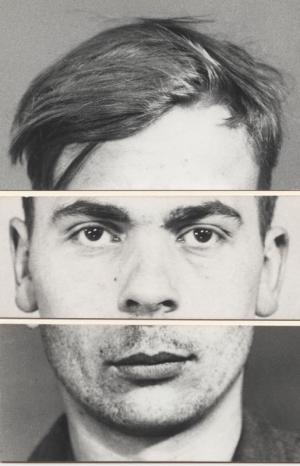

Identify

Photography quantifies and measures; it allows us to recognise, to identify. Thus, at the end of the 19th century it became a precious tool for police. Mug shots began to appear in criminal files and the first wanted posters to tackle the problem of re-offenders. Bertillon set up the first anthropometric database that used pictures and different measurements of the human body. The method was applied to increasingly broader swathes of the population, stigmatised as dangerous or potentially threatening: anarchists, nomads, political opponents, especially in the colonies… In France, the first identity cards with photographs were created in the 1890s. Identity cards for foreigners, French people, civil servants, exit and transit visas, residency permits, Ausweis under the Occupation… the administration counts, categorises, investigates, supervises.

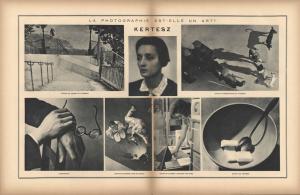

Thirties

In the early thirties, photography became more experimental. It brought a broader repertoire of shapes and scenes to modernity, with new and founding attitudes. According to the artistic, social and political evolution of the time towards global transformation, photography’s “Nouvelle Vision” envisaged the visible through the geometry of bodies, factory materials and the beauty of the machine. In describing modern bodies, in photographing revolutionary architecture, in the scenography of a portrait, the photographer removed all that was superfluous from the frame. Today, we can only stand back and admire the common oeuvre of the “New Vision”, that owes everything to German and Hungarian immigrants, to the banished, the Jews, women and communists who made French and Parisian photography the melting pot for the renewal of the medium.

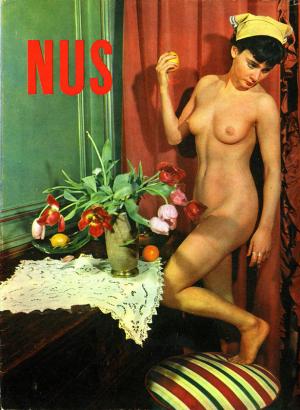

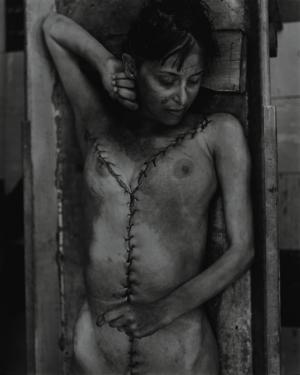

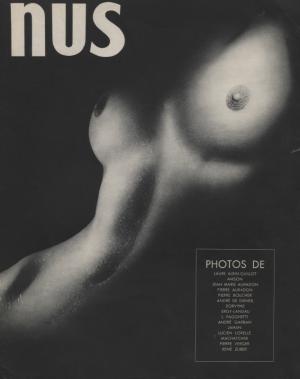

Nude

In the 19th century, photography perpetuated the tradition of the artistic nude as practiced in the fine arts. The body was treated as a study, an academic notion. While modesty remained the norm, and despite censorship, this did not prevent the proliferation of erotic images that made the nude photography’s first source of income. As early as the twenties, photographers highlighted the aesthetic qualities of the nude, in tandem with the widespread movement of liberation for the body in general. It was generally shot close-up, fragmented, starkly; it became a pure, aesthetic object sculpted by the light. In parallel, a type of erotic and kitsch photography continued to circulate under the table (Horace Roye). Today, free from censorship, photography has dispensed with traditional criteria of beauty and place the body, face and sexual organs in the same shot.

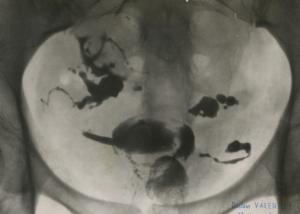

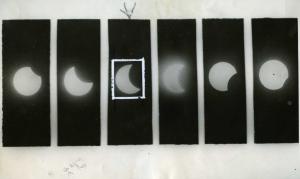

See beyond

The technical precision of photography that was boasted about from the very start, allowed the world to see beyond its field of perception. The photographic plate offered a huge range of detection: every tiny point of light could be captured as long as the brightness levels were high enough and the length of time sufficient. This is how photography certified the existence of some stars that had heretofore only existed on a page through mathematical calculations. It was also with a photographic plate that Röntgen revealed X rays in 1895. Photography allowed precise observation, the accumulation of details could be studied and identified making it useful to scientific progress. Many medical disciplines took it over such as psychiatry. Photography became the instrument that was essential to demonstration. Taking things further and affirming that it provides proof was but a step away, a step taken by certain unscrupulous “spirits”…

Publishing

Publishing brought photography to another level. From the illustrative in early 20th century newspapers, it led to the implosion of the traditional magazine just after the First World War, making photography the main player in modernity. The photographer became a reporter. The world was from then on seen with a subjective eye. Roto-engraving was to change everything and emancipate the image from the text. Every week, the reader got not only an illustration of the world, but the world itself. The image was no longer alone, it became part of a series. The double page grabbed the reader’s eye. Visual culture was born. These magazines provided visibility for photographers and their first critiques.

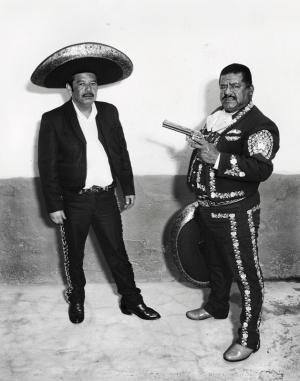

Current photographic art

The museum’s support for current photographic art takes various forms: acquisitions from photographers and galleries, grants to support projects or our artist in residence programme. The latter enables a photographer to conceive and produce an artistic project with the added advantage of the experience and availability of the museum’s photographic lab. This has meant that Virginie Marnat-Lempoels got a chance to explore female stereotypes at her leisure, such as the rich American lady surrounded by a décor that tells so much of her social origins. On the other end of the scale, Jake Verzosa did a series of portraits of the last tattooed women of the Kalinga tribe in the Philippines. Marion Gronier attempted to capture the feeling of abandonment of circus artists who go from the lights of the ring to the anonymity of their temporary dressing rooms. Stan Guigui depicted the misery and violence of El Cartucho, Bogota’s cour des miracles and joined the Mariachi community for a time… Photography is universal and the points of view on show here are multiple.

André Mérian : Water Front

As part of a commission for the “Marseille Provence European Capital of Culture », André Mérian photographed the ports of the Mediterranean, questioning unscrupulous urban sprawl, the result of property speculation. It is far from banal when for the first time in the history of geology, such huge transformations have been carried out to the structure of the landscape. For a photographer who choses to represent real landscapes, there is more sadness in depicting this world than in praising the beauty of the view. In the tradition of Marville or Atget, he records the passage from one world to another, showing us the end of a myth.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

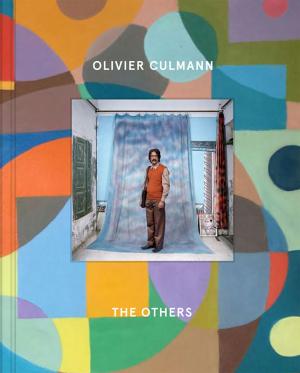

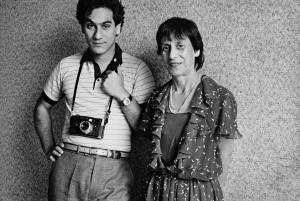

Olivier Culmann

The Others

10 17 2015 ... 01 17 2016

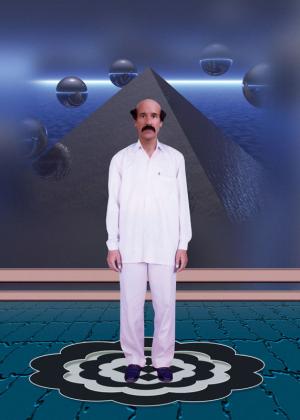

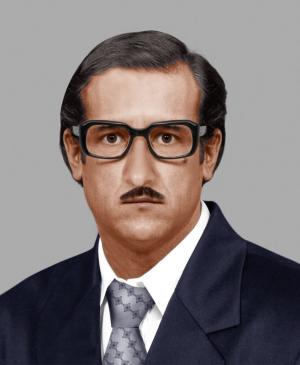

Olivier Culmann presents us with a strange portrait gallery. The Indian man appears in many forms before our eyes without ever revealing his true identity…

Olivier Culmann began to shoot this series between 2009 and 2011, when he was living in Delhi, and kept shooting up until 2013. The Others will be presented in full for the first time at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce. In a series that includes over 130 photographs, the photographer questions the way in which social status is elaborated through the construction of self-image and explores the limits of the photographic medium.

The Others is an examination of the codes of Indian society and their modes of representation. The photographer’s basic material is a series of self-portraits. In each one, Olivier Culmann applies the visual and sartorial specifics that define each Indian to himself. In a society as compartmentalised as India’s, he means to highlight the variety of elements that make up the identity of an individual: religion, caste, class, profession, geographical origin…

The portraits are split in four phases, according to the different iconographic creative processes in India: neighbourhood photography studios, Photoshop used by digital labs, painting…

__

Phase 1: portraits taken in a photography studio

The studios represented in these shots are neighbourhood studios in different Indian cities, notably in Delhi and the surrounding regions, Chennai, Pondicherry and Mumbai.

__

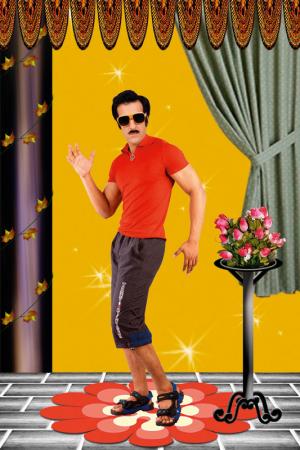

Phase 2: portraits using digital equipment

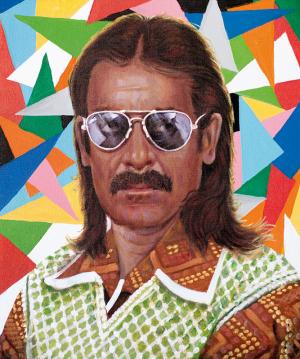

In the neighbourhood studios, a range of backdrops is often available: a patterned curtain, a photographic mural or a landscape painted on the wall itself. When a client comes to have his or her photograph taken, they can also borrow various items of clothing (jackets, shirts, ties…) for the duration of the shoot. With the advent of digital technology, backdrops are easily created on the computer. The client, whose silhouette is cut out in advance, can thus choose the backdrop (reconstituted studio backdrop, Swiss mountain scape, Taj Mahal…) in front of which he or she wishes to be pictured.

Photographers also offer the option of the already well-dressed and well-presented headless body, on to which the client’s head can be attached and slid into place by the retoucher/photographer. Faceless bodies are also available (hair and ears are part of the package), as are various types of headgear (hats, berets, turbans…), hairstyles, various accessories (armchairs, couches, bouquets of flowers…) and frames with motifs.

The phase 2 portraits blend this digital material with the faces on the initial portraits.

__

Phase 3: recomposing and colouring damaged photographs

Repairing family photographs that have been damaged (by time, damp, ripping…) is common practice in India. It is often done when someone dies to restore an emblematic photograph of the deceased. The photo is usually seen on the wall at home or in the family business. It is a guarantee of filiation and its symbolic meaning seems more important than the actual faithful reproduction of the ancestor’s physical traits. In line with this practice, Olivier Culmann gave various digital retouching labs half a torn photo. He then asked them to reconstitute the face entirely and to colour the photo as they saw fit. Some added backdrops.

__

Phase 4: paintings from photographs

Painting on photographs is common in India, especially for shop signs and more traditionally for film posters. Using this skill set as a base, Olivier Culmann gave a Delhi painter a number of black and white photographs and asked him to paint them in different styles (mostly from film poster types). Just like with the repair work, he let the painter choose the backdrops and the colours.

The original paintings will be on show in the exhibition.

__

Olivier Culmann

The Others

This exhibition was co-produced with Tendance Floue and Central Dupon Images.

With support from Canson, Olympus France, La Souris sur le gâteau and the Hôtel St Georges in Chalon-sur-Saône.

All of the photographs for this exhibition were printed on Canson gloss 310g premium paper in the laboratory at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce.

A tie-in book is available from Editions Xavier Barral.

Publication /

The Others

Olivier Culmann

Editions Xavier Barral

Bound & covered

21.5 x 26.3 cm

196 pages

Approx. 140 colour photographs

Texts: Christopher Pinney, lecturer in anthropology and visual culture at London’s University College, François Cheval, Director of the Musée Nicéphore Niépce and Christian Caujolle, Associate Lecturer at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure Louis Lumiere, critic, independent curator.

__

Extracts:

Clothing oneself is no longer a functional necessity for humans, and has not been since time immemorial. The act of clothing oneself has transmuted into a game ruled by social convention. Appearance decides, even configures the real. The fictional lives that follow one another in the New Delhi studio are no more illusory than the “real” pseudo-images that come before. Faced with these decorated scenes, the only “incontestable”’ objects, we rediscover the consistency of likelihood. By playing with pretending, the photographer exhumes the weight of destiny that covers us. The shapes, colours and textures are all signals we address to our peers; the ones we want to stand out from! Faced with the inevitable, we put on the rags and adopt the attitude that others have determined for us.

Each photograph, or more to the point, each scene, is an event that is both derisory and perfectly apt. The portraits compose a collection of short stories. They do not pretend to reduce the different components of the Indian population to farce, but merely to reflect the spirit of the times. In the harsh light of the studio, these reconstituted lives rise above a reality that is never recognisable and is always unintelligible. In the knowledge that we are aware of the state of the world, rather than giving us the same photographic narrative on the Indian sub-continent, Olivier Culmann gives us his fugitive impressions. Freed from the weight of the past, his portrait-prototypes are notations, better, as narratives. The various elements of the image are clues to interpret and to bring the spectator closer to others in the hopes that they will end up with a fabric of hypotheses at their disposal. The apparently unrelated objects, the poses and situations form a logical chain to be reconstituted.

[…]

What we present to others is an ideal of the fantasised figure, the seal of identity. However, here, identification is inseparable from dissimulation. The figure’s make-up and poses redefine the character’s visibility levels. The subject, or the person, is in no way a “natural” being. In this constant swing from the norm and the search for one’s own identity, the person attempts to constitute him or herself into a coherent unity. This demand for originality pushes them to contemplate their own reflection. The mirror becomes his digital print. They search ceaselessly for faults, as if trying to spot the deliberate mistake. Anxiety reigns in this surreal world. One hunts down the imperfections that go against the self-image they desire so deeply. This concern for appearances, deliberately encouraged by merchandise, is at odds with self-awareness, singularity and autonomy. The particular attention given to one’s appearance is aided and abetted by technology. Digital identity is built in communication spaces where individuals contemplate themselves in a narcissistic manner from a closed-off space. The connection to others remains a never to be satisfied quest. And photography, despite its immense ambition, can’t do a thing about it.

[…]

Two excerpts from a text by François Cheval

Published in The Others

By Editions Xavier Barral

Olivier Culmann: Biography /

Social conditioning and free will are intrinsic to Olivier Culmann’s work. Located somewhere between the absurd and the derisory, his work puts the question of our everyday lives and our relationship with images under a microscope. He always comes back to his obsessions – and ours -, winning us over with his sense of humour and his talent for narrative.

1993 – 1999: In collaboration with Mat Jacob, his Les Mondes de l’école project was awarded the Villa Médicis Hors Les Murs in 1997

2001: Les Mondes de l’école

, published by Editions Marval

Une vie de poulet

, published by editions Filigranes

2003: Scam Roger Pic award for “Autour, New York 2001 – 2002” series

2004: Intouchables , published by Editions Atlantica

2006: His “Watching TV” series was presented at the Rencontres internationales de la photographie d’Arles

2008: The “Les Mondes de l’école” series is shown at the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

3rd

World Press Photo prize for his “Watching TV” series (“contemporary subjects” category)

2011: Watching TV

, published by Editions Textuel

“Watchers” show at the Pavillon Carré de Baudouin in Paris

2014: The Others and Diversions series shown at the Festival Images in Vevey, Switzerland

2015: The Others

series is shown at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône

The Others

, published by Editions Xavier Barral

__

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Nicéphore Niépce’s heritage

10 17 2015 ... 01 17 2016

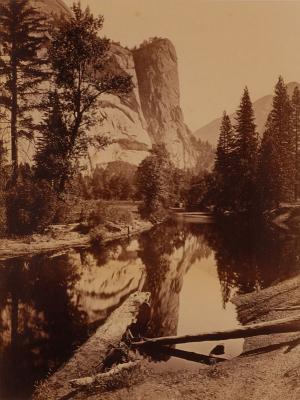

250 years after his birth and two centuries after the experiments that led to the world’s first ever photograph, what remains of Nicéphore Niépce? His now uncontested founding work continues to inspire artists today.

We know that the man was talented, with an intelligence powered by curiosity. Nicéphore Niépce’s life as a researcher and inventor indeed offers a striking example of stubbornness and fervour. He was infinitely tenacious, he experimented empirically from a place of naivety. For him photography, the mechanical image, was a new continent: « I am like Christopher Columbus when he made his late but certain discovery of a new world… We are moving forward with probes in our hands, on our boat of adventure; and soon the crew will all shout… land! land!!! [A letter from Nicéphore Niépce to Alexandre du Bard de Curley, “Au Gras, le 24 mai”, BnF, fonds Janine Niépce] »

He reached land in 1824 with the development of the heliograph. Finally the action of light on a photo-sensitive surface allowed an image captured in a camera which then could be reproduced and fixed. Le Point de vue du Gras taken by Niépce circa 1826 – and considered as the oldest photograph currently in existence [Coll. Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas, Austin] - consisted of a tin plate onto which Niépce managed to “record” the view from his window in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, outside Chalon-sur-Saône.

Nicéphore Niépce’s legacy has no antecedents and made us a people of images, inhabitants of a new continent inhabited by him alone. But in the uncertain world of contemporary culture, Niépce’s intervention has taken on so much importance that it has become the very definition of modernity. We still don’t have the measure of its effects, even better, the strange consequences. The open window is in fact a Pandora’s Box that the heirs to the genius inventor never cease to explore.

This exhibition is dedicated to these heirs. From Paolo Gioli to Daido Moriyama, it shows how contemporary creation has taken over both the character to which it renders homage but also of the result of his experimentation that it gleefully reinterprets.

Daido Moriyama’s

devotion to Niépce thus brought him on a pilgrimage on the tracks of the inventor, from Saint-Loup to Austin, Texas. “As soon as I found myself faced with this view [Saint-Loup-de-Varennes], the image of shadow and light from Niépce’s iconic photograph started to replace the real landscape in front of my eyes and suddenly, I had the feeling that I could see through Niépce’s eyes.”

A reproduction of Le Point de vue du Gras

hangs over the bed in the photographer’s Spartan room “so as not to forget the origins and essence of photography.”

This Point de vue

that has been badly reproduced so often is part of everyone’s unconscious. It comes through in a photograph by Bernard Plossu

taken by chance during a trip to Portugal from the window of the train he was sitting in.

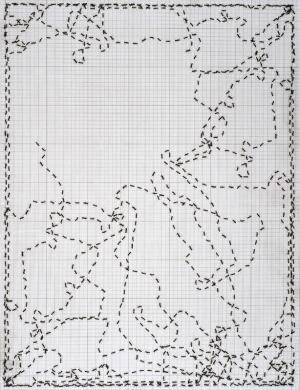

The same photograph inspired Andreas Müller-Pohle for his Partitions digitales I (1995). Le Point de vue du Gras was digitalised then reborn in code as a series of alphanumerical signs.

Raphaël Dallaporta , opened the helio-engraving image file of the Cardinal of Amboise [Helio-engraving from the collections of the musée Nicéphore Niépcewith word processing software]. In the resulting immense series of abstract characters he then wrote the secret coded figures used by Niépce in his correspondence with Daguerre. The resulting final image contains the trace of the interaction between the two inventors.

The omnipresence of computers now allows Niépce’s work to be reinterpreted in ways that go from the most mathematical to the most zany. Joan Fontcuberta recomposes Le Point de vue du Gras in the form of a photo-mosaic of images found on Google Images. Olivier Culmann transforms Niépce’s posthumous portrait painted by Léonard François Berger [ Painted in 1854, over twenty years after the death of the model; this painting is kept at the musée Nicéphore Niépce], in an Indian portrait studio [A reference to his series The Others , which was shot in India and is on show at the same time at the musée Nicéphore Niépce], overdoing the digital retouching.

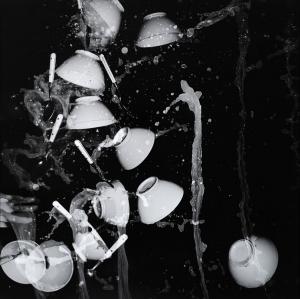

Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand’s homage comes through the constant redefinition of the basics of the mechanical image backed up with the scientific history of photography. His credo is to discover and experiment with old techniques. With the Gouttes de Niépce , he takes shots of landscapes through drops of gelatine that work as lenses that he then superimposes on the image of the same blurred landscapes. “In this laborious home-made effort, one should see a nostalgic quest for photography’s primitive years when everything was yet to be discovered with a box, a piece of glass, some chemistry and the element of chance.”

This reworking of the photographic medium is at the centre of the work produced by Paolo Gioli as an homage to Niépce. At the end of the seventies he shifted into Polaroids, experimenting with its potential like someone discovering the past, reinterpreting Niépce’s iconic images using new materials.

The variety of viewpoints brought to the table by a group of photographers with such singular origins and careers is evidence of the wealth of Nicéphore Niépce’s legacy.

Artists:

Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand (France, 1945)

Lars Kiel Bertelsen (Denmark)

Alexandra Catière (Belarus, 1978)

Olivier Culmann (France, 1970)

Raphaël Dallaporta (France, 1980)

Joan Fontcuberta (Spain, 1955)

Ralph Gibson (United States, 1939)

Paolo Gioli (Italy, 1942)

JH Engström (Sweden, 1969)

Daido Moriyama (Japan, 1938)

Andreas Müller-Pohle (Germany, 1951)

Bernard Plossu (France, 1945)

Emmanuelle Schmitt-Richard (France, 1968)

In tandem with the exhibition:

12 photographers pay homage to Nicéphore Niépce in letters accompanied by their “first photograph” or the shot that made them become photographers.

The texts are brought together in a book entitled

“Cher Nicéphore…”

Editions Bernard Chauveau

Texts by Sylvie Andreu and François Cheval, and the photographers: Jean-Christophe Ballot, John Batho, Elina Brotherus, Raphaël Dallaporta, Valérie Jouve, J.R., Mathieu Pernot, Bernard Plossu, Reza, Patrick Tosani and Sabine Weiss.

48 pagesISBN: 978 2363061515

20 €

(To be published in August 2015)

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

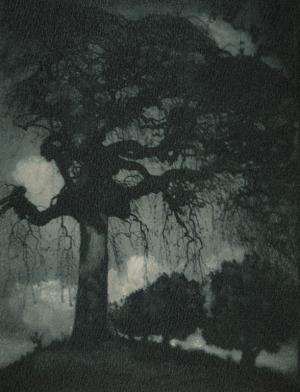

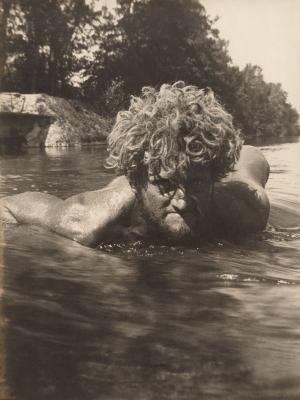

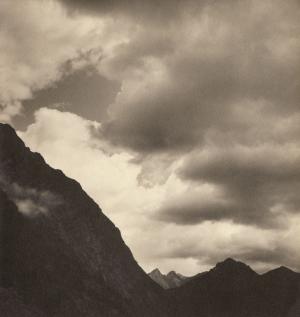

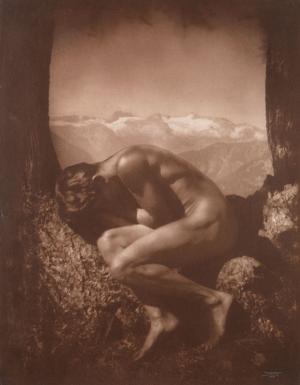

Rudolf Koppitz

[1884-1936]

06 13 ... 09 20 2015

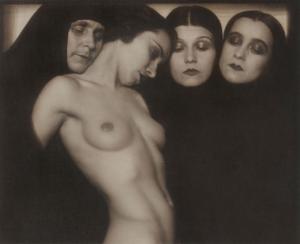

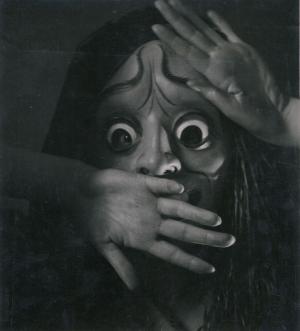

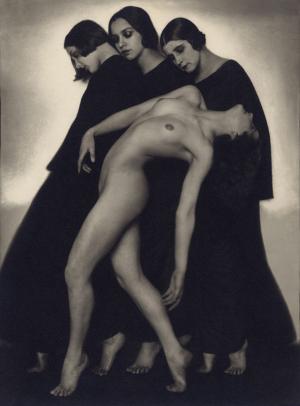

Heir to the Viennese Jugendstil and Pictorialism, the photographic work of Rudolf Koppitz [1884-1936] magnifies the body in movement in elegant compositions that have become iconic in the history of photography. The “Rudolf Koppitz [1884-1936]” exhibition is the first big retrospective of the photographer’s work in France. It was curated by the Photoinstitut Bonartes, Vienna and brings together almost 130 photographs and documents in one unique exhibition at the musée Nicéphore Niépce.

In 1929, the first ever article on art photography was published in the Encyclopaedia Britannica . The illustration used was a photo by Rudolf Koppitz, Movement Study : we see three women draped in black in front of whom is a fourth young woman, nude, leaning backward in an elegant and controlled stance. This photo has since become a veritable icon for the way it incarnates art photography and seems to come from another time when modernity was expressed through the Nouvelle Vision and Surrealism. It was in this context nevertheless that Rudolf Koppitz [1884-1936] would become one of the main figures of Viennese pictorialism. This international movement came to be in the 1880s with groups of rich amateurs in clubs claiming the status of art for photography as a whole. To do so, it put the emphasis on what it referred to as “noble” forms of printing, inspired by painting and the graphic arts: pigmented prints, using gum bichromate, oil… The pictorialists refused the purely mechanical reproduction of the real by stylising, interpreting, blurring…

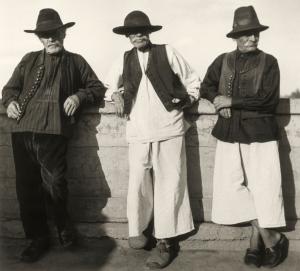

Koppitz was one of the representatives of this aesthetic. His position as teacher then director of the photographic department at the Vienna Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt [ The Institute for applied graphic arts] allowed him to exercise an influence on Viennese photographic output in general. He participated in a number of exhibitions and this, as well as presiding over selection committees, conferred a certain authority on him in art photography circles. Koppitz’s themes throughout his life are evidence of his predilection for nature and physical exercise, with an attachment to the principles of naturism that appeared at the start of the century. His depiction of nudes, including of his own body, reflected an aesthetic quest for strength and purity.

In the early thirties, Koppitz shifted away from pictorialism and adopted a more documentary, but still carefully staged style. He travelled the countryside in search of peasant authenticity. These images of the Austrian “Heimat” became popular at a time when there was an attempt to increase tourism: the State wished to depict an ideal homeland, a country of beautiful Alpine landscapes, and keeper of traditions.

[The term “Heimat” has no real equivalent in English. It reflects the notion of the homeland, native land, country, but also evokes a place that feels like “home”].

Koppitz’s aesthetic vocabulary was adopted by the Austro-fascist powers and the supporters of National Socialism. Koppitz’s own political opinions remain unclear, he died two years before the Anschluss. We are more familiar with those of his wife Anna, also a photographer and his assistant, who took a number of shots of Austrian and German youth that are aesthetically reminiscent of the work of Leni Riefenstahl. She continued to exploit her husband’s work after 1936 and by associating her own photos and her links to the Nazi regime doubtless contributed to damaging Koppitz’s reputation in the long term. Was Rudolf Koppitz naive or merely guided by his artistic and aesthetic quest? His works have a timeless and theatrical beauty that earned him the praise of his peers and a level of popularity for his nudes and dance photographs that has lasted until now.

BIOGRAPHY

Rudolf Koppitz was born on January 3rd 1884 in Austrian Silesia [in the current Czech Republic] into a German-speaking family.

1897-1907

The young Rudolf became an apprentice to the photographer Robert Rotter in Freudenthal. In 1901, the young man, who was then 17 years old, passed his professional aptitude certificate and got a job in Florian Gödel’s studio in the main part of the Opava district. A year later, he moved to Brno, where he worked retouching on positives and negatives in Carl Pietzner’s famous studio.

1908-1911

In the following year, Koppitz worked for a number of different photographers throughout the country. He moved to Vienna in 1911. His first dated photographs, taken in his spare time, go back to 1908; they are of the Minoriten and St. Charles’ churches in Vienna, picturesque landscapes or cragged mountain views. His style was influenced by painting and the graphics of Art Nouveau and the Viennese secession, as well as those of the photographers of the pictorialist movement that he must have seen on show in Vienna. However, there is nothing to prove he had any direct connection with these various movements.

1912-1913

At the age of 28, Koppitz took a new direction in his photographic career by taking a course at the Vienna Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt [ The Institute for applied graphic arts]. He followed the specialist course by Novak on the artistic photographic portrait. Novak’s evident taste for the ornamental and his predilection for stylised compositions and the way he worked spaces in light and dark sections, had a lasting effect on Koppitz. In 1913, Koppitz was hired as an assistant for “portrait and landscape photography and retouching”. He preferred to work with the techniques of “noble” printing, that he continued to perfect, and tended to choose typicalpictorialist subjects: snow-covered landscapes, trees, veduta

, romantic country scenes and many portraits. He travelled through Europe, notably to Holland and Italy, where he took many photos.

1914-1918

Koppitz was drafted right from the start of the war and had to interrupt his work as assistant. He was made sergeant in a company of pilots and named “master assistant for field photography”. He first served on the Eastern front before being transferred to the photographer reconnaissance training site in Wiener Neustadt. The photos that remain from this time represent the Galician front that Koppitz romanticised in his characteristic style. Shots he took from his planes are clean, geometric, modern compositions and stand out clearly from the rest of his work.

1919-1927

When the war ended, Rudolf Koppitz went back to his job at the Institute for applied graphic arts. He was first the “master assistant for retouching”, then became a fully-fledged teacher in 1920. He became a member of the Photographic Society. In 1924, his first big personal show was held at the Vienna Chamber of Commerce. He began actively participating in other shows: up until his death, his work was seen in almost 60 shows in Austria and abroad. He met Anna Arbeitlang at the Institute, where she had been working as an assistant since 1917. They were married during the summer of 1923. Koppitz took his first nude photos in collaboration with his young wife. In early 1925, Koppitz produced his best-known work, Bewegungsstudie

[Movement study], that went on to be an international success. During this creative phase, he worked with a number of dancers. He notably photographed the members of the Russian dance troupe “Issatschenko Ballet” twice.

1928-1929

Koppitz did not just participate in international amateur photography exhibitions, as a committee member he also decided who else got a chance to participate in this type of event. He was part of the staff of the magazine Der Lichtbildner and this, as well as his numerous other photographic contributions to other trade magazines Photo- [und Kino-]Sport

or Photographische Korrespondenz

, meant he had quite a level of influence in the contemporary photography field in Austria.

1930-1935

In 1930, the international “Film und Foto” [ FiFo] exhibition took place in Vienna. Koppitz’s style changed: the symbolist compositions were replaced by shots that were more documentary and objective. He no longer used complicated printing process and shifted away from the pictorialist blur. His favourite motifs remained country life, landscapes and sport.

1936

“Land und Leute” [ The Country and the People], was Koppitz’s biggest and final exhibition, inaugurated at the Museum of the Applied Arts [now the MAK] in Vienna in February 1936. Over five-hundred pieces were exhibited with motifs depicting a romanticized view of rural life in Austria and South-Hungary.

Rudolf Koppitz died on July 8th 1936 at the age of 52. Anna Koppitz administered his heritage and continued to work as a photographer, especially during the Nazi era.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

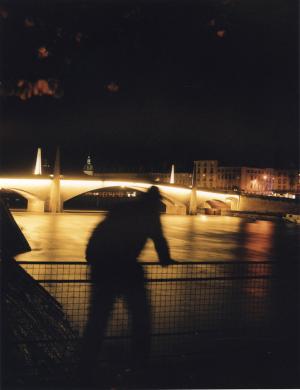

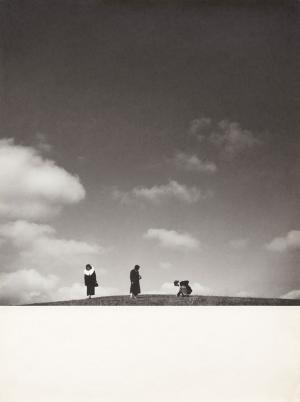

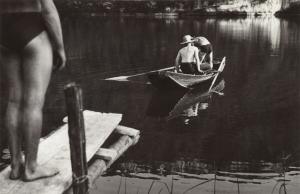

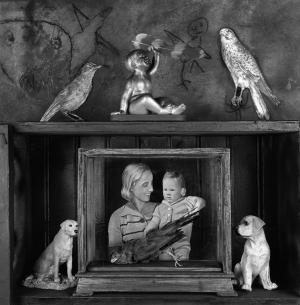

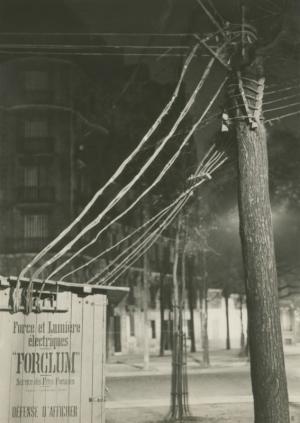

From 1924 to 1962, Théodore Blanc and Antoine Demilly ran one of Lyon’s best known studios. They were renowned for their portraits and dedicated their lives to photography, sharing their time between traditional commercial photography and their inventive and fertile creative work.

For over forty years, Antoine Demilly’s daughter has been gathering together the work of her father and his partner that was dispersed or thrown out once the studio closed down in 1962. Conservation was not on the cards at the time; photography was not high on the list of priorities of French institutions, and even less so the work of a seemingly banal local studio. The task was immense as Blanc and Demilly were prolific. Thousands of portraits were produced in their studio where the bourgeoisie of Lyon were regulars, as were the avant-garde artists. The photographers’ personal work was just as consequential. The variety of subjects, now often unidentified, bear witness to the eclectic taste of the two partners who, even though they often worked separately, always refused to disassociate their names.

This exhibition presents a part of this collection reconstituted as it was. The original prints are difficult to date due to damage over time and lack of care. The thirties blend into the fifties, united in the same quest for iconographical poetry.

Blanc and Demilly loved beautiful pictures and were conscious of progress so they varied their expressions, going from a pictorialist tendency to the vocabulary of the “Nouvelle Vision”. Their early adoption of the Rolleiflex and the Leica which were so easy to handle, provided them with a freedom of movement that was heretofore unimaginable. They paced the streets of Lyon, the banks of the Saône, the mountains and the surrounding countryside where they often brought groups of amateur photographers, sharing their passion.

While the activity of the studio concentrated for the most part on portraits that they modernised by removing background décor, their curiosity and taste for experimentation pushed them to other subjects, from the most poetic to the most formal. Blanc and Demilly were in favour of multiple perspectives, all subject to emotion. To grasp life at its most picturesque, most unexpected, the subject could be slight, a shadow with clean lines expressed with a simple, almost abstract composition, thus making it beautiful as if the banal were being elevated to the metaphorical. They revealed latent objects, shapes in strange light and the mist of the early morning or of twilight. These “atmospheric” simulacra were filters. They force the viewer to go beyond the raw reality of things to attain a certain visual poetry. The eye is required to lose itself in the image.

These photographs are at times disconcerting. Blanc and Demilly appear to collect locations of a “new world” whose history we do not need to know. Things that are only expressed in wanderings or solitude are silently hidden there.

But this apparent eclecticism does not mean dispersion. Each image confirms that by going beyond simple vision, we can see all of its mystery and beauty for ourselves. For Blanc and Demilly, that which is accessible to the senses gives life to a certain truth. The photographs record and transmit vibrations, indeterminate moments of the sensuality of the world. They are reflections. From one image to the next, we come onto something new. Photographic wanderings, between objects, portraits and landscapes are but a vagabond and unruly practice for the eye. Photographic modernity provides us with the possibility of multiplying our viewpoints, that is to say the experiences of a “new world”, an exploration of the near that is also a question of self-knowledge.

The photos in the exhibition come from the Julie Picault-Demilly collection.

The exhibition is co-produced with Stimultania

, photography centre.

Each year, Stimultania programmes exhibitions, residencies, mediations, concerts and various cultural events.

The exhibition coincides with the publication of a book:

Blanc et Demilly, le nouveau monde

Texts ; François Cheval, Céline Duval and Xavier Fricaudet

Lieux Dits Editions, Lyon, 2015

120 pages - 85 ill.

ISBN : 9782362191183

27,00 €

Blanc and Demilly: a timeline

Théodore Blanc (1891 – 1985)

Antoine Demilly (1892 – 1964)

1924 : Théodore Blanc and Antoine Demilly become partners under the name “Blanc et Demilly” and take over the studio of their father-in-law Edouard Bron, a portraitist and photographer in Lyon.

1933 : They take part in the “L’image photographique de Daguerre à nos jours” exhibition at the Braun gallery in Paris.

1933 – 1936 : Aspects de Lyon : 121 helio-engravings gravures in ten volumes.

1935 : They make a splash with the inauguration of one of the first galleries dedicated to photography. They show their own work as well as that of amateur photographers.

1938 : They win the gold medal for Portraits during the 15th photo and cinema exhibition in Paris.

1942 : Charme de Lyon , is published, illustrated with twenty-seven of their photos.

1947 : They show their work for the first time at the Salon national de la photographie at the Bibliothèque nationale. They continued to take part until 1959.

1951 : The gallery closed.

1962 : The Blanc et Demilly studio is sold after a few declining years. The collection of prints was dispersed.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Patrick Zachmann

Mare, Mater

02 14 ... 05 17 2015

Using fixed and moving images, Patrick Zachmann compares his own family story to that of today’s migrants. He tackles their relationship to the sea they cross and the mother they leave behind. He builds his narrative around the relationship between mothers and sons, between men and women.

It consists of a voyage, a voyage of memories and exiles. This voyage weaves together the threads of all those destinies I encounter: those of the migrants who leave their countries on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, fleeing unemployment, boredom, the lack of a future;of the women, the mothers, who let them go or discover they have already left. And for myself, I embark on a voyage to discover my mother’s roots, the ones she wants to forget.

This adventure that starts in Marseille and spreads over a period of two years led me to Issam, a young, undocumented Algerian migrant from Annaba who had arrived a few months previously and was already in a homeless shelter; then to Nizar, an illegal Tunisian national that I met in the street just after his arrival from Lampedusa on a makeshift boat. They both tell the story of their journey but, above all, give the reasons for leaving home and, in their own way, how much they miss their mothers. The mother figure that is sacred in Judeo-Arab culture. Underneath, we find out that in addition to poverty, they also fled a way of life, a sense of smothering, and perhaps even the mothers that adore them (perhaps too much?).

It’s the story of the Mediterranean, the story of the sea, the story of the mothers. Sometimes the sons don’t come back. Sometimes, the sons die at sea. And the, there is also the dream, the fantasy. The dream of a Europe that will never be as beautiful, as welcoming, as rich, as when seen from the other shore.

I went there, where they come from, to try to understand, to meet their mothers and listen to their side of the story of their sons’ departure, the wrench, the long separation.

This project comes also from the certainty that in the near future, I too will have to face up to my definitive separation from my own mother who is old and ill. Her death will make it impossible to ever get any answers on the gaps in her life story. The mother-son separation for which I am preparing myself, resonates with the separation that these illegal immigrants that I have filmed and photographed, that they force on their own mothers when they cross the sea in life-threatening conditions to come North.

I started to ask her questions and film her. She was 90 years old and afflicted with the beginnings of Alzheimer’s disease and she didn’t remember much, especially the details of Algeria, but she did remember how eager she was to forget.

I didn’t have any photographs – an irony for a photographer – nor any accounts of the history of my mother’s Sephardic Jewish family. She wanted to forget Algeria, the poverty, forget her origins.

Today, I take the voyage in reverse. I voyage into lost origins, the part that is missing, hidden, eliminated.

I am certain that I became a photographer in order to create a missing family album, both on my mother’s side and that of my father whose parents were deported to Auschwitz and Birkenau. I need to make memories.

So this project is the a blend of the narrative of my difficult relationship with a mother that I wanted to escape from a very young age and that in a way I have come back to in her dying days, and the perilous sea crossing of all these young migrants who leave their mothers crazy with worry on the shores of their childhood. The connections between these two worlds reflect an examination of the basics of my work as a photographer and journalist, my relationship to time and memory and my never-ending quest for identity.

Mer (sea), mother, mare, mater… Yet again my photography echoes my own story and attempts to fill the gaps.

Patrick Zachmann

Exhibition co-produced with Magnum Photos in the context of Marseille-Provence 2013, European Capital of Culture and Fotografia Europea, Reggio Emilia 2014.

A book has been published to coincide with the exhibition:

Patrick Zachmann, Mare Mater, journal méditerranéen

, foreword by François Cheval, ed. Actes Sud, 2013.

312 p + 1 DVD of the film Mare Mater

(54’’)

ISBN : 978-2-330-02395-9

Prix : 39 €

Patrick Zachmann : Biography

Since 1976 Patrick Zachmann (b.1955), has devoted himself to long-form photographic essays that evoke the complexity of the communities whose culture and identity he examines. In 1982, he entered the violent universe of the police and the Mafia in Naples. Then, he began a long personal project exploring Jewish identity: Enquête d’identité (Investigation of identity

). In 1989, his reportage of the events in Tiananmen Square was widely published in the international press. I was awarded the Prix Niepce. He’s part of the tradition of travel photographers who scrutinise the trace of History or search for timeless objects.

Patrick Zachmann is a member of Magnum agency.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français