Northern Ireland :

Gilles Caron + Stephen Dock

02.12 ... 05.22.2022

Opens Friday 11 February at 7 p.m.

Fifty years after the events of Bloody Sunday, this exhibition blends the historic and the contemporary to broach the Northern Irish question in all its complexity.

The Northern Irish conflict, commonly referred to as “The Troubles”, began in 1968. It tore a corner of Ireland apart, between republican nationalists (Catholic for the most part) and loyalist unionists (Protestant for the most part). It all began with a civil rights movement against the institutional segregation that mainly affected the Catholic minority. The rise of paramilitary organisations on both sides led to the situation escalating rapidly. The Irish Republican Army led a campaign of terrorist attacks mainly between 1969 and 1972. Northern Ireland descended into civil war.

This was a War of Independence for the nationalists and a fight for survival for the Unionists. From the very beginning, Gilles Caron was there to record the many facets of this extremely complex conflict.

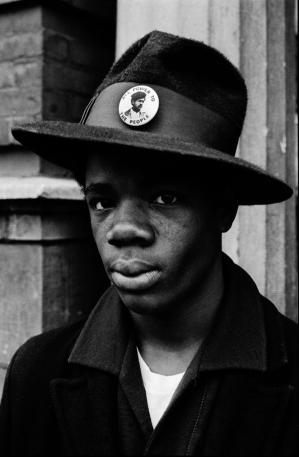

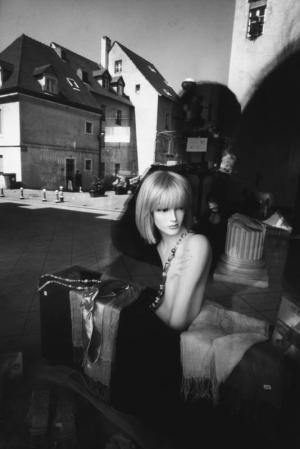

Gilles Caron

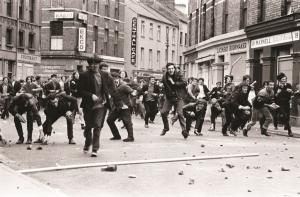

Northern Ireland - 1969

On August 12 1969, the Derry chapter of the Apprentice Boys, Unionist Protestants and members of the Orange order, held their annual parade close to a working-class Catholic neighbourhood, despite protests from the locals. This led to the Battle of the Bogside, thought by many to be the start of “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland. The British Army rolled in with tanks and tear gas as nationalists fought back with stones and Molotov cocktails. Two days later, while other uprisings were brewing elsewhere in the province, the British Army attempted to take back control. These events marked the beginning of a war that was to last thirty years.

Gilles Caron was in Derry on August 12, covering the Orange march for the Gamma photography agency. He had a feeling the violence was escalating and once he got there, he very quickly understood what was at stake.

It’s quite simple.

I was in

I

reland before anyone else.

The evening before the figh

ti

ng broke out,

I had arrived to cover a march.

Everything was calm, quaint even. The marchers

walked

by

peacefully

in

their

hats

with flowers in their lapels. A fight broke out around four o’ clock in the afternoon.

It started slowly, a few rocks were thrown, and t

hen it got out of hand as the protesters set fire to entire neighbourhoods. It went on like that for three days. We thought it would end as soon as it started.

In Paris

,

they thought

there was no point in

send

ing

someone. The demonstrators took the arrival of the British Army to be

a victory for the Catholics.

I thought it was all over and I was goi

ng to leave when things started up again in

Belfast.

I took a taxi from Derry to Belfast.

I worked all day and all night

then

got on a plane to London a

nd

gave my photos to a passenger who was

flying on

to Paris. That meant that Gamma had the originals the following day

before the slow coaches in the English papers

. The guys from Paris Match arrived on the Saturday

when I was leaving

.

”

[1]

Gilles Caron captured the tension as it built, from the first photos of the marching bands to the first rocks thrown. Very quickly, the police seemed to be overwhelmed and the city became a battleground. Gilles Caron watched as the shift occurred, this was not his first experience of armed conflict as he had covered the Six-Day War, the Vietnam War and Biafra. Through his lens, we see a country at war.

Gilles Caron’s work in Northern Ireland was published by many news magazines around the world and contributed to the conflict getting coverage very early on. In an issue dated August 30 1969, Paris Match

presented its readers with a full portfolio of five double pages of just photographs.

Recently, a book by Pauline Vermare

[2]

entitled Insurrections

provided a complete review of the reportage archives and a written piece of reference. She points out: “These pictures evoke the gaiety of May 1968 and the gravity of the armed conflicts that Caron covered. This tension is what makes this reportage so powerful. By following history in the making, hour by hour, day and night, from Derry to Belfast, Caron is the only person who was there to bear witness to the fundamental turn things were taking for the people of Ireland: state of peace, state of siege, state of war.”

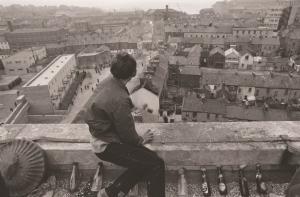

In addition to being “first” on the scene, the modernity of Gilles Caron’s photographic approach makes it exceptional. His work is in constant movement, shot/ reverse shot, from the top of a building, at the corner of a street; in one camp, then in the other. He gets close to the scene, he goes, he comes back, and stops at a strategic spot. At times it feels like he is ahead of what’s happening.

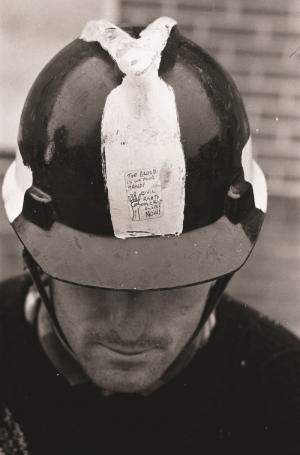

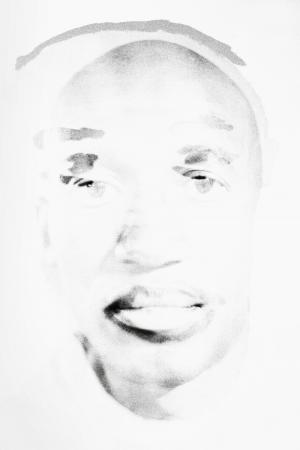

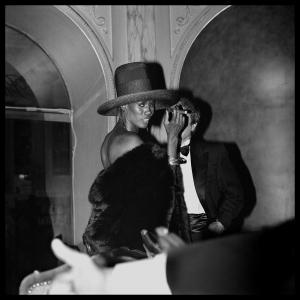

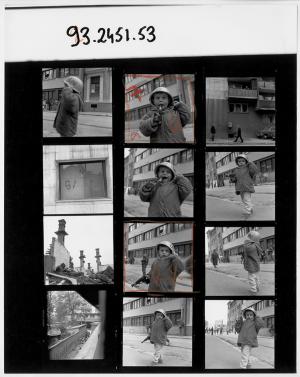

In the middle of the chaos, he pays attention to individuals, main characters or anonymous figures. He takes the portrait of Bernadette Devlin, a leading figure in the civil rights movement in Derry, and that of a young boy with a gas mask that ended up on the cover of Paris Match, icons both. That picture even became the subject of one of the world-famous murals in the Bogside. Other shots, away from the reportage, do not seem destined for a newspaper. Street scenes or portraits away from the conflict, help to build the narrative, to express the tragedy. Through these pictures, Gilles Caron invites the viewer to question themselves and opens the way to new forms of photojournalism.

In his book Gilles Caron, Le conflit intérieur

[3]

, Michel Poivert writes: “Caron’s ambition was to talk about the news in a different way, to integrate his own feelings about humanity to the visual stenography of photojournalism. This attempt to find a new frequency between the outside and the inner life now seems like a foreshadowing of the following decade’s auteur

photography.”

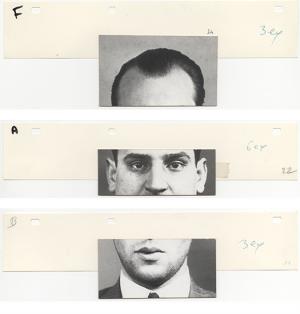

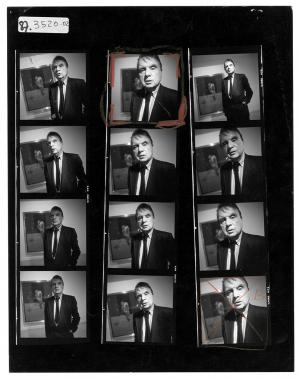

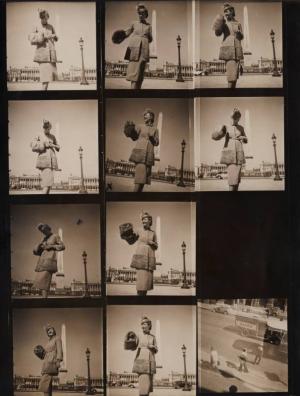

In four days, sixty-two black and white rolls of film and almost three hundred colour shots, Gilles Caron crafted one of his greatest stories; a unique testimony of this turning point in history. Visitors to this exhibition will get to discover his work, beyond the iconic pictures published in the press at the time. It includes seventy photographs, vintage and modern prints, as well as enlarged reproductions of contact sheets that highlight the photographer’s process.

The museum would like to thank the Fondation Caron, the Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine and

Fannie Escoulen for their support in putting this exhibition together

.

[1] See Jean-Pierre Ezan, interview with Gilles Caron, Zoom n°2 March-April 1970

[2] See Gilles Caron, Insurrections, Irlande du Nord 1969 - Text by Pauline Vermare - Editions Photosynthèses, 2019.

[3] See Gilles Caron, Le conflit intérieur, Editions Photosynthèses, 2013

Stephen Dock

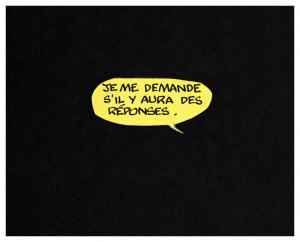

Our day will come

Our day will come. The popular Irish Republican slogan evokes the hope for freedom and the wish to vanquish the other side. Words that cannot be said without thinking of the day of our own death.

Stephen Dock started as a photojournalist at a very young age. In 2008, when he was barely twenty years old, his only ambition was to seize the moment. Ever eager to inform, he followed stories to the world’s most dangerous hotspots, Syria, Palestine, Mali, Iraq... War zones became his chosen field, conflict an everyday occurrence. Very soon however Stephen Dock started to ask himself questions. Was he attracted to battlefields because of his own pain, his own inner conflict? His soundless stories expressed his personal battle, the inability to find peace.

Dock decided to take a different path, he started working in a blend of colour and black & white, enlarging certain details, reframing stories. The approach was more personal, the writing more poetic. Photography allowed him to talk about the world and talk about himself. Inside and outside were no longer disconnected. As Gilles Peress puts it “He always photographs from the inside to the outside and not the other way round” freeing up his side step.

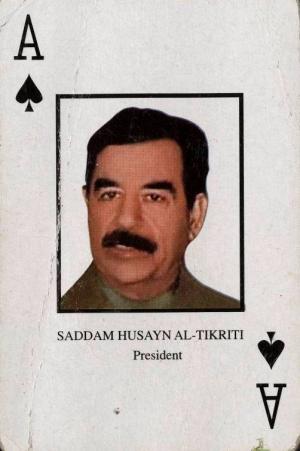

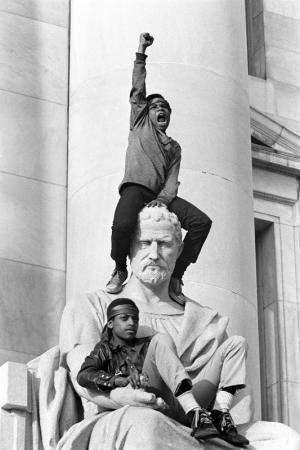

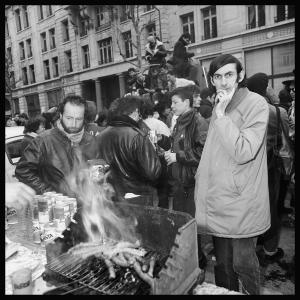

The “New IRA” formed in Northern Ireland in 2012. Stephen Dock decided to go to Belfast for the centenary of the Ulster Unionist pact. The tension was palpable, but nothing happened. The time for armed conflict was over. The Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, putting an end to thirty years of civil war. But the souls of the people were not at rest, and ancient foes lived together in a fragile peace.

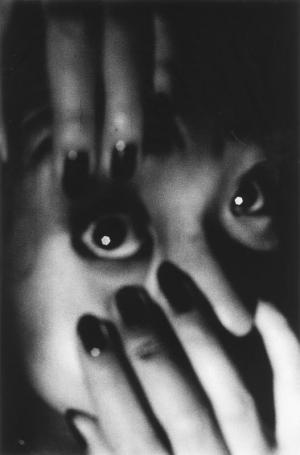

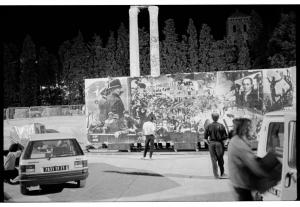

People from both sides of the conflict are, to this day, haunted by an inner violence that is cultural, social and political. It marks the faces of the survivors and those of the younger generations. It wields a power much stronger than physical violence, shaping behaviour, becoming an invariable that is handed down from one generation to the next. If the hate between communities sculpted Northern Irish identity, it has also left a long-lasting mark on the province. Life goes on around the “peace lines”, the “peace walls” that began to appear after August 1969. Dotted around the cities of the province, they separate the inhabitants of the same neighbourhood, at times even the same street. The stigmata of war are everywhere. Huge murals pay tribute to the “heroes” of the conflict, painted messages warning strangers that they are entering republican or unionist territory. The walls speak. Graffiti shows allegiance to dissident groups, voicing support for those in prison, or protesting the occupation: “Brits out!”

Marching season is an annual event, with parades, marches and bonfires of wood palettes that can reach thirty metres high, on which the Irish flag is burned, or the Union Jack. Each event is deeply political and underscores the partition. The division is entrenched affecting daily life down to the tiniest detail.

The question for the photographer was how to render this latent conflict that has opposed two communities for hundreds of years? How was he to represent a society that is this divided? To find an answer, Stephen Dock travelled to Northern Ireland eleven times in six years. He tried to understand the impossibility of peace, something he felt himself. The resulting body of work is made of things and signs from everyday life: portraits, architectural details, street scenes… The photographer chose traces, at times infinitesimal, left by the conflict, and made them visible.

Biography:

Stephen Dock was born in 1988 in Mulhouse. He lives and works in Cambrai.

From very early on he worked in the field, travelling to Venezuela, to Nepal, to the West Bank, to Syria, to Iraq, to Northern Ireland, to the United Kingdom, to Mali, to the Central African Republic, to Lebanon, to Eritrea and to Indian Kashmir. He was represented by VU’ from 2012 to 2015 and was a finalist in the Leica Oskar Barnack award in 2018, finalist in the Prix Découverte Louis Roederer in 2020 special prize-and winner of the Prix LE BAL for young artists from the ADAGP in 2021. His work has been shown at the Leica Gallery during Paris Photo, the Tbilisi Photo Festival, the Visa pour l’image festival, the CNAP, the MAP Festival in Toulouse and at the Bayeux Festival. He has been published in French and international publications such as M le magazine du Monde, Le Figaro Magazine, Newsweek Japan, Paris Match, Internazionale, VSD

and Libération.

The museum would like to thank Canson and Fannie Escoulen for supporting this exhibition

.

The prints were developed and printed in the museum’s laboratory on Canson Infinity Arches 88.

Stephen Dock’s work was produced with support from the CNAP - Centre National des Arts Plastiques.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Laurence Leblanc

Où subsiste encore (Still remains)

from July 2 to September 25 2022

Opening : Friday, July 1 at 6:30 pm

Photography is generally considered to be able to faithfully reproduce the real. The most common uses of photography as a medium are for its reproductive qualities: illustration, journalism, science, etc. Photography, as an instrument of memory, comparison and knowledge-sharing also records our memories and, in doing so, marks the passage of time; it has been part of our everyday lives since its invention and digital technologies have ramped up its importance to the extent that it is now omnipresent.

These affirmations tend not to apply to the output of photographer Laurence Leblanc. Her work takes us to Africa, Cambodia, Brazil and Cuba where she introduces us to children, nuns, dancers and musicians. However, we do not get to know them or the countries they live in as her motivation, down the years, has not been to record in order to document, but instead to grasp the invisible, to capture that which cannot be recorded in a photograph: the imperceptible thread that links humans, both to one another and through the ages.

Everywhere she goes, she is. Laurence Leblanc absorbs her surroundings, connects with the locals and lives alongside them. She queries, understands, learns. She stays for protracted periods, and often returns to the same places. She shoots instinctively, her work is subjective and benevolent as she seizes the shot delicately, with no premeditation. The photographic act is set off by a feeling, the photographer collects the result.

Back in her studio, time tends to stretch. She takes time, with her photos, her contact sheets, her working prints. Another form of silent, solitary absorption occurs. Before she shares them, the photographic images that will feature a lived experience must stand out, they must provoke questions, enquiries and doubts.

Laurence Leblanc speaks of capturing the inner energy and emotion that we all share. It is quite the challenge as it involves depicting that which is intangible. But she does. Leblanc brings her uncompromising auteur’s gaze to bear through this prism alone. The photographs she chooses to show are emotional echoes of the ties that bind people, things and the world.

This exhibition voluntarily blends different series, from Rithy, Chéa, Kim Sour et les autres

(2003) to the hitherto unseen Du soin

(2021) as for Laurence Leblanc, it makes no sense to identify groups, establish a chronology or outline a theme; her work is an ever-renewed attempt to keep that which is invisible but still subsists, alive and perceptible, despite everything: the tenuous, fragile but essential ties that bind.

Curator:

Sylvain Besson, musée Nicéphore Niépce

The museum would like to thank La Société des Amis du Musée Nicéphore Niépce and Canson.

The prints in this exhibition were produced in the laboratory of the Musée Nicéphore Niépce on Canson® Infinity Baryta Photographic II 310 g/m² paper and Canson® Infinity Rag Photographic 210 g/m² paper.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

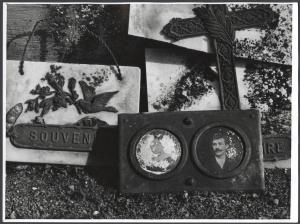

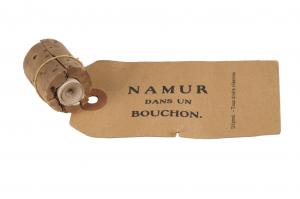

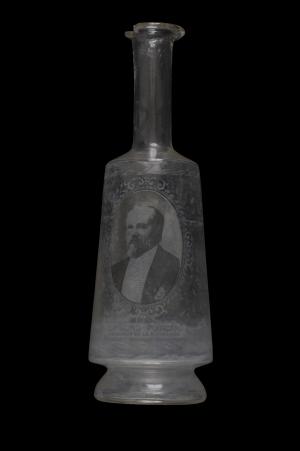

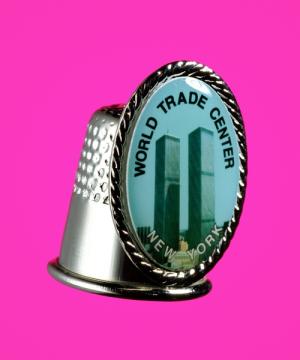

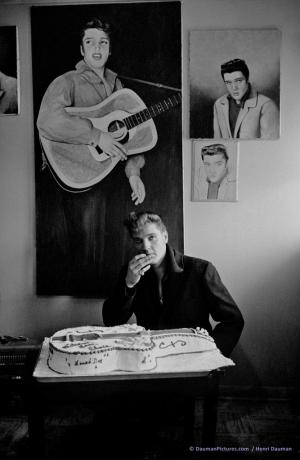

Penser / Classer : 50 ans du musée,

hommage à Georges Perec

from July 2 to september 25 2022

Opening :July 1 at 6:30

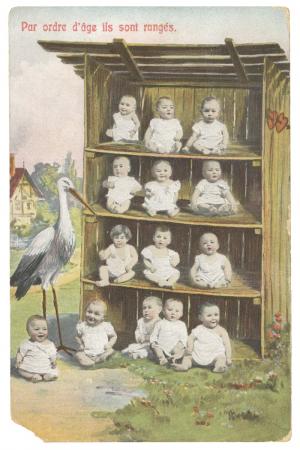

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, the Musée Nicéphore Niépce (1972) will lift the veil on what the public never sees: the storage rooms, the wealth of its collections. It is impossible to show everything, and even making a representative selection is difficult. An upcoming catalogue will retrace the history and the museum’s acquisition policy. Consequently, in order to give a feeling of the diversity and size of the collection and avoid doubling up with the permanent one, this approach is more poetic. The idea is to invite the public in to have fun with the spaces, inspired by Georges Perec.

Perec (1936-1982), known as the “mad taxonomist” was an adept of classification, lists and inventories. In an essay entitled Penser / classer

(Think/ Classify

), he ironically questions this anthropological obsession with trying to impose order on the world. Humans feel the need to sort through the world in order to understand it, to think it through. A place for everything and everything in its place. This overriding “obsession” is at the heart of museum life and activity. Regardless of its field of expertise, a museum acquires, sorts, classifies, preserves, transmits and shows.

This has been the mission of the Musée Nicéphore Niépce for fifty years, focussed on one subject, photography.

Images within images.

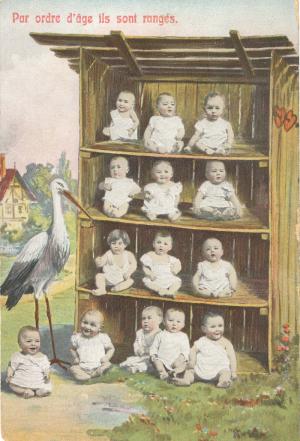

From the very beginning, photography carried a fixed idea, a utopia, at its heart, born out of the revolutions of the 19th century. The belief that through photography, we can show everything, and bring the entire world into a museum. The belief that we can make a universal and exact statement about things, and preserve a living image. The belief that we can win out over the passing of time, forgetting and destruction. Furthermore, the belief that we can better know and understand the world, by detailing, unpicking, examining it from every angle, from the infinitely huge to the infinitely tiny.

Photography kept its side of the bargain as is evident from the storage rooms of the musée Nicéphore Niépce. For two centuries, photography has, without a doubt, fulfilled all of our individual or collective taxonomic obsessions, whether they are scientific or documentary, amateur or artistic. The nature of the museum’s collections and the way they are organised can sometimes bring on a form of Perec-ian dizziness. Perec’s lists can also be applied to photography: “arrange, catalogue, classify, cut up, divide, enumerate, gather, grade, group, list, number, order, organise, sort”

. Then “subdivide, distribute, discriminate, characterise, mark, define, distinguish, oppose, etc”.

However, contrary to what they entail, none of these operations can be said to be objective. There is no such thing as neutrality and exhaustiveness. Everything comes with a certain perspective, decisions made in advance, off camera.

Thankfully, as Perec reminds us with humour and humility, our quest for omniscience is doomed to failure. By the time we finish them, our attempts to organise knowledge are often obsolete, and perhaps “barely as effective as the initial anarchy” …

Curator: Emilie Bernard, musée Nicéphore Niépce

The museum would like to thank Sylvia Richardson, Bernard Plossu, the Société des Amis du Musée Nicéphore Niépce and our partners, the Maison Veuve Ambal and Canson.

![Henri Schliemann Atlas des antiquités troyennes. Illustrations photographiques faisant suite au rapport sur les fouilles de Troie [218 planches] Paris Maisonneuve et Cie 1874 tirages sur papier albuminé © Coll. musée Nicéphore Niépce Henri Schliemann Atlas des antiquités troyennes. Illustrations photographiques faisant suite au rapport sur les fouilles de Troie [218 planches] Paris Maisonneuve et Cie 1874 tirages sur papier albuminé © Coll. musée Nicéphore Niépce](/var/ezflow_site/storage/images/exposition/actuelles/50-ans-du-musee/antiquites/58464-4-fre-FR/antiquites_smartphone.jpg)

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Think / Classify : 50 years of the museum,

part 2

10.22.2022 to 01.22.2023

The second part of the Think / Classify exhibition invites the public to continue discovering the museum's collections with a renewed display of works.

To celebrate its 50th anniversary, the Musée Nicéphore Niépce (1972) will lift the veil on what the public never sees: the storage rooms, the wealth of its collections. It is impossible to show everything, and even making a representative selection is difficult. An upcoming catalogue will retrace the history and the museum’s acquisition policy. Consequently, in order to give a feeling of the diversity and size of the collection and avoid doubling up with the permanent one, this approach is more poetic. The idea is to invite the public in to have fun with the spaces, inspired by Georges Perec.

Perec (1936-1982), known as the “mad taxonomist” was an adept of classification, lists and inventories. In an essay entitled Penser / classer

(Think/ Classify

), he ironically questions this anthropological obsession with trying to impose order on the world. Humans feel the need to sort through the world in order to understand it, to think it through. A place for everything and everything in its place. This overriding “obsession” is at the heart of museum life and activity. Regardless of its field of expertise, a museum acquires, sorts, classifies, preserves, transmits and shows.

This has been the mission of the Musée Nicéphore Niépce for fifty years, focussed on one subject, photography.

Images within images.

From the very beginning, photography carried a fixed idea, a utopia, at its heart, born out of the revolutions of the 19th century. The belief that through photography, we can show everything, and bring the entire world into a museum. The belief that we can make a universal and exact statement about things, and preserve a living image. The belief that we can win out over the passing of time, forgetting and destruction. Furthermore, the belief that we can better know and understand the world, by detailing, unpicking, examining it from every angle, from the infinitely huge to the infinitely tiny.

Photography kept its side of the bargain as is evident from the storage rooms of the musée Nicéphore Niépce. For two centuries, photography has, without a doubt, fulfilled all of our individual or collective taxonomic obsessions, whether they are scientific or documentary, amateur or artistic. The nature of the museum’s collections and the way they are organised can sometimes bring on a form of Perec-ian dizziness. Perec’s lists can also be applied to photography: “arrange, catalogue, classify, cut up, divide, enumerate, gather, grade, group, list, number, order, organise, sort”

. Then “subdivide, distribute, discriminate, characterise, mark, define, distinguish, oppose, etc”.

However, contrary to what they entail, none of these operations can be said to be objective. There is no such thing as neutrality and exhaustiveness. Everything comes with a certain perspective, decisions made in advance, off camera.

Thankfully, as Perec reminds us with humour and humility, our quest for omniscience is doomed to failure. By the time we finish them, our attempts to organise knowledge are often obsolete, and perhaps “barely as effective as the initial anarchy” …

Curator: Emilie Bernard, musée Nicéphore Niépce

The museum would like to thank Sylvia Richardson, Bernard Plossu, the Société des Amis du Musée Nicéphore Niépce and our partners, the Maison Veuve Ambal and Canson.

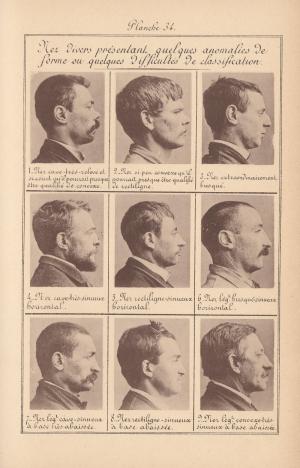

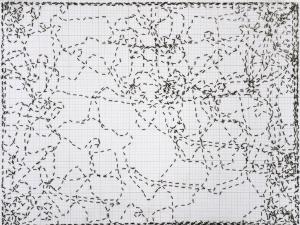

Entre sciences et poésie, le « photographe-physicien » Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand (1945) travaille sur la matière, l’espace, le temps, le mouvement, avec les principes originels de la photographie. Ici, il s’agit de mesurer et révéler le trajet d’une fourmi sur du papier millimétré. « La construction de ces images est complexe (enregistrement du parcours, sélection des différentes attitudes, collages, tirage via des papiers huilés, etc) mais cette jonglerie technique n’a guère d’importance pour moi. Avant tout, c’est un hommage à ces voyageuses qui, pendant nos siestes sous un arbre, dépassent largement les frontières de notre transat. » (Patrick Bailly-Maître Grand)

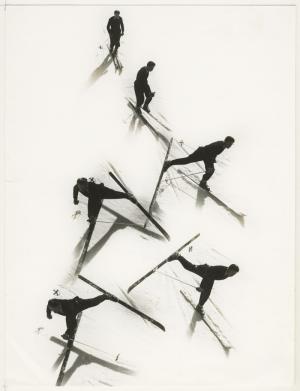

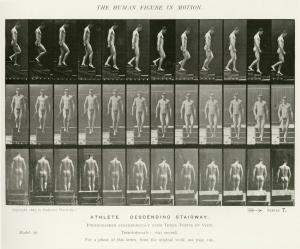

Le britannique Eadweard Muybridge (183O-19O4) inspiré par les travaux d’Étienne-Jules Marey(chronophotographie), invente en 1878 un dispositif photographique de décomposition des mouvements, composé d’une douzaine d’appareils à déclenchements successifs. Ces nouvelles représentations font l’objet de deux livres, Animal locomotion, et The human figure in motion. Muybridge, comme Marey, font figure de précurseurs du cinéma.

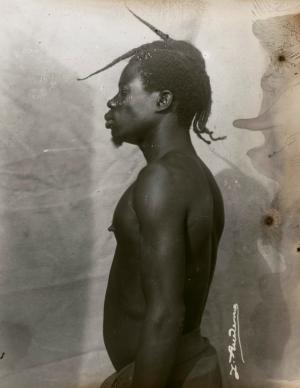

Membre de l’administration coloniale en Afrique équatoriale française, les photographies de Jean François Audema (1864-1921), représentant les populations et les activités coloniales, sont éditées et diffusées en cartes postales avec la mention « Collection J. Audema ». En 1897, alors qu’il est en poste à Luango (Congo), il photographie le passage de la mission Belge Behagle-Bonnet de Mézières et celui de la mission Marchand. Le musée Nicéphore Niépce conserve un ensemble de 71 plaques de verre de cet auteur et de cette période.

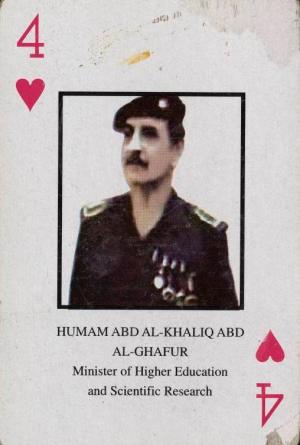

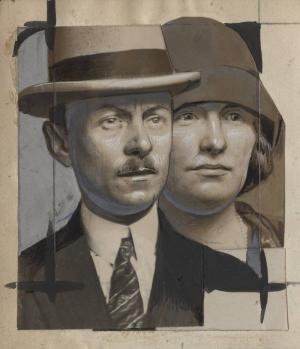

Par l’exercice du photomontage (découpage, collage) pratiqué dans ses archives personnelles, Christian Milovanoff (1948) associe des images, qu’il en soit l’auteur ou non, et les fait résonner entre elles. Cette mise en ordre du chaos visible crée du sens, des récits, entre documentaires et fictions

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Madeleine de Sinéty

A village

10.22.2022 to 01.22.2023

Inauguration Friday October 21, 7p.m.

Following on from the shows at the Gwinzegal Art Centre in Guingamp and the Musée de Bretagne in Rennes, the Musée Nicéphore Niépce presents “Madeleine de Sinéty, A Village”.

The show features 120 photographs that trace ten years of the photographer’s life and work, with an additional forty shots that were not part of previous iterations.

Madeleine de Sinéty’s work comes with a journal that is both factual and personal, and covers a wealth of iconographical categories that includes family photographs, portraits, reportage and ethnographical studies.

When photography was invented, people suddenly became visible as they were. According to the light they reflected, their imprint could now appear on a light-sensitive surface. This major anthropological event opened the way for the documentation and study of absolutely everything: monuments, landscapes, but also peoples. Ethnography took full advantage of this, but photography is, above all, a form of representation. People make themselves available and photography merely interprets; we can only presuppose the objectivity of the document, nothing more. This potential for truth in a photograph therefore requires a historical, social and cultural framework, in addition to inside knowledge of the mental structures that presided over their creation.

[1]

Madeleine de Sinéty’s work involves understanding how individuals relate to one another, tracking the traditions that tie them together and uncovering personal and collective stories. Regardless of their status, it is undeniable that these photographs tell us much about an era and a community. They provide an attentive account of a social reality: a rough life, still without electricity or running water, in some cases, and with few mechanical tools. A vision of the precariousness of an agricultural world that was on the way out. Contrary to the ethnologist who must always keep “one foot in and one foot out”, Madeleine de Sinéty did not keep her distance. On the contrary, she shared the lives of her subjects. She was fiercely attached to people, and her long-term commitment to her subjects was decidedly unscientific.

A close look at the photographs and an in-depth study of her writings tells us that her project is truly something else. It appears to be based on an inner need, detached from any form of functionality in terms of the pictures. Madeleine de Sinéty is looking for an “elsewhere”, an intimate elsewhere that signifies a break and a significant life change. Her background is aristocratic, and as a small child, she resented never being allowed to venture onto the farm attached to the family chateau: “I came to Poilley (…) completely by accident. I was living in Paris and knew nothing whatsoever about the countryside, even though I had spent most of my childhood summers in Valmer, my great-grandmother’s Renaissance chateau in the Loire valley. From my third-floor, attic-bedroom window, over the French-style gardens and the high stable walls, I could see a corner of the farmyard. I would spend hours watching the cows enter and leave the stables, listening to them moo, watching the farm children jump in the hay and the long-haired horses slowly pull the high-sided wooden trailers with big, iron-clad wheels. I could hear the shouts and the laughter, the wheels clattering on the farmyard cobbles, the high-pitched whistle of the thresher. I could smell all of the farm’s smells, the freshly-cut hay, the warm cow-pats, the fermenting milk, but I was not allowed to go. The farm was off limits to the children of the château.”

Years later, she got the urge to discover this elsewhere that seemed so close. She wanted to move to the country, discover another life, and to do so she would have to integrate, to truly take part in the everyday life of the community, over a long period.

“(…) I decided to stop for the night in the most remote village I could find. The following morning, I awoke to the sounds, shouts and smells of the farm of my childhood. I always travel with my bicycle in my car, so I took it out and went for a spin around the surrounding countryside. For the first time ever, there was no one to prevent me from entering the farm. I went back to Paris to resign from my job as an illustrator and set about organising my new life in Poilley.”

Things were not easy in the beginning. She took to wearing wooden clogs and was seen as eccentric. It was even said in the village that she was a spy! She had her moments of doubt, but her interest in life as it was lived in Poilley was genuine. She really got involved, working hard, making no concessions. She shared the everyday lives of a number of families as they worked the soil, planting, harvesting, calving, making hay, slaughtering pigs… taking part in farm life in every season. The locals got used to her presence and to her camera.

Her close relationships with her subjects can be seen in her photographs. She allows the villagers to come into the frame naturally, until they eventually become consenting players in the project. They end up trusting her to “see their own story”: “I began photographing Poilley in colour and every now and then I would invite the village to a slide show. We had to carry extra benches from the church to the dirt-floored village hall in order to seat everyone so that they could admire their own lives and work. Amid the shouts and laughter, they were surprised to find they were so beautiful.”

Madeleine de Sinéty photographed stories, big and small, and catalogued them all in her journal. Every evening she would write down everything she had heard during the more or less formal interviews, and would plan what she wished to photograph the following day. She gave equal importance to the banal and the extraordinary. She set down unforgettable quarrels between families, accounts of how to grow beetroot, a calculation of how many potatoes bought a pair of clogs, and unfailingly recorded the precision and indifference of movements that are repeated thousands of times to the rhythm of nature: a woman tossing hay, a man striding through a field, children playing in piles of apples… She experienced this world. She did not just build a visual representation, she added smells, noises, feelings… Looking at the pictures today, the emotion can still be felt. Through photography, today’s viewers can access a real sensory and emotional experience.

In the late sixties, French rural communities had been shoved into modern times and were having a hard time coping with this sea change, in particular the consolidation of land holdings. They were bewildered, stuck between peasant farmers and farm “operators”. Madeleine de Sinéty was only too aware of this development. She knew she was not recording the future of agriculture, as mechanisation and monoculture were soon to become the rule.

Over time, her photographs, in typical seventies slide colours, have taken on a new resonance. They bear witness to customs and a way of life that have disappeared, to a life of immense freedom and natural generosity, to a pace of living where speed was not an issue, to a time past where farm animals were known by their names, “Coquette”, “Bijou”… The before-times, that are of particular relevance to us today.

“The work is hard, but this house is so peaceful, I want to live here, rocked to sleep by the slow ticking of the clock in the hall. The work is hard, but regular. Day after day, we calmly dig, labour, prune and water to be rewarded with wheat and summer fruit.

Then it starts all over again, quietly, without haste, anxiety or fear, and each year feels like the one before, as if we could live forever.”

Madeleine de Sinéty.

The book :

Madeleine de Sinéty, Un village

Editions GwinZegal

23x21 cm

188 pages

ISBN : 979-10-94060-28-5

[1] André Rouillé « Le document ethnographique en question »

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Yannick Cormier

Tierra Magica

02.12 ... 05.22.2022

opening : friday february 11th / 7pm

It feels like a fever dream. Like a strange nightmare. In the early-morning mist, the trees seem to take on human form, the bushes grow legs and walk forward with a determined gait, human tissue becomes bark, or the other way round. Elsewhere, horned beings, covered in animal skins, feathers, even blood, wearing grimacing masks, forming a cohort that we join with fear, fascination or even enthusiasm. Sometimes, these creatures from a distant-past hurl abuse at passers-by, pretend to kidnap young women, or fight one another. At times they allow themselves to be hunted, to be mistreated by the crowd then judged by a court, whose verdict is unsurprising: at daybreak, they disappear in the bonfire.

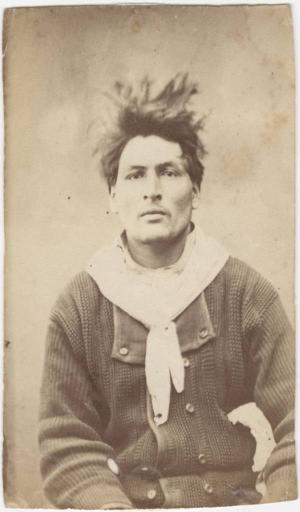

Yannick Cormier immerses himself in the carnival rites of Portugal and North Western Spain in a manner that is truly his own. He brings no pre-established protocol, no aesthetic pretention or need to make an inventory to the table. Other photographers have already done that. 19th

century anthropologists systematically captured the faces and profiles, making an inventory of the masks, accessories and costumes, reducing ancestral rites to the status of folklore. More recently, meticulous and spectacular photographic directories, laid out with technical exactitude and method, brought these figures back to the present in an almost anachronical way.

These pictures, however, are intended to go beyond all that, to the border between the visible and the invisible, between fear and hope, between pagan beliefs and religious beliefs. Unruly, turbulent and transgressive, these photos are imprinted with the pulsation of the crowd, revealing the vital forces at the very origins of carnival. Yannick Cormier takes the viewer on a journey to the heart of the tumult and strangeness of these festivals, all of which share the common thread of marking out time, transgressing established order and reminding society of its intangible connection to nature. The seasons follow one another, life is perpetually reborn. Death, as tragic as it may be, is very much part of life. Cormier blends these parades with archetypal landscapes, like so many fantastical visions, depicting forests that could be the belly, the forge, but also the place where these unsettling creatures fade into the mist.

These festivals were banned by Franco in 1937 as they encouraged unrest and rebellion, and were never officially rehabilitated. Instead, they became events of political and cultural resistance. They are still around today and circumstance has made them synonymous with a new form of disobedience. For those who wish to be at one with others, to frolic in a packed crowd in a life-saving burst of freedom.

Biography

Yannick Cormier was born in France in 1975. In 1999, he joined Astre studio in Paris. He started off working as an assistant to Patrick Swirc, William Klein and many others for magazines like Vogue, Flair, Elle, Vanity Fair. He then became a news photographer and had his work feature in French and foreign publications like Libération, Le Nouvel Observateur, Courrier International, The Guardian, The Hindu, CNN...

Cormier lived in India from 2003 to 2018, where he continued his photographic explorations while developing other activities. In 2007, he founded Trikaya Photos Agency, based in Chennai (Tamil Nadu), a collaborative platform for photographers working in India, who were interested in the political, social and cultural issues facing a society that was constantly changing before their eyes. Between 2011 and 2016, Yannick Cormier also curated a number of exhibitions for the Chennai Photo Biennale and Pondy Photo (Pondicherry).

During this period, he began to document the rites, celebrations and festivals of the Dravidian people in Southern India (from the Sanskrit “Dravida”, which means surrounded by water on three sides). “In Tamil Nadu, in the south of India, the most far-back, ancient traditions have remained intact. The powerful presence of spirits and living Gods are incarnated behind the masks, in the release of the bodies during the rite and in the animal bodies during the sacrifices. We can no longer tell if they are men, Gods or spirits, as they live their real and divine, natural and supernatural truth. Men and women in a trance rushing into the darkness, in broad daylight…” His immersive process creates pictures that suggest more than describe, leaving space for the artist’s own feelings of fascination, astonishment and exaltation. These pictures were published in 2021 under the title Dravidian Catharsis

, by Le Mulet.

Yannick Cormier’s interest in jubilant crowds, ancient traditions and lasting archaic rituals found a new outlet when he moved back to Europe. His experiences of carnivals in Portugal and North-West Spain rekindled his attraction for forms of resistance to the uniformization of the modern world. Somewhere between the sacred and the profane, mysticism and paganism, not unlike the subject, Cormier explores these festivals, oscillating between fiction and reality, in Tierra Magica

published in 2021 by Light Motiv. His research into the borders between the real and the spiritual is ongoing, under the title Pagan Poem

.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Alexis Cordesse

Présences

oct. 15 th 2021 ... jan 16th 2022

opening : thursday oct.

7 pm

Alexis Cordess / anglais

The prints of series Itsembatsemba

and Juliette

for the exhibition were produced in the laboratory at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce on Canson Infinity Rag Platine 310 g. and the series La Bruja

on Canson Infinity Baryta Prestige 340g paper.

The museum would like to thank: Canson, La maison Veuve Ambal and La société des Amis du musée Nicéphore Niépce.

Publishing:

Alexis Cordesse,

Talashi

Atelier EXB,

Éditions Xavier Barral

Bilingual French-English,

16,5 x 23,5 cm

128 pages

55 photographs in color

35 euros

Isbn : 978-2-36511-318-2

In library,

Oct. 7th 2021.

Presences

Today’s networks and the flood of data have led to the trivialisation of press photography. Digital technology has turned each and every one of us into potential witnesses and producers of pictures. This instantaneously uploaded content creates the illusion of a hyper-visible world orchestrated by huge media networks that dictate a regime of urgency and immediacy. There are so many pictures out there that we zap more than we look. The sheer volume of content means each quickly glanced at/ quickly forgotten picture is given the same weight. When timeframes are so short and the present is all that matters, there is little room for analysis or long reportage work that requires time, thought and long-term involvement. Alexis Cordesse was born in 1971 and started working as assistant to Gianni Giansanti in 1990, before going to work as an intern at the Sygma photo agency. The following year, he took his first photographs in Iraq, at the end of the first Gulf War, a war “without pictures” that was to push news coverage into the age of suspicion. His influences came from photojournalism but he soon found himself straining against the confines of press photography. Formats and layouts dictated editorial decisions and magazines tended to consider photographers as mere illustrators. Print media was already suffering from the onslaught of television news since the early seventies, and in the early nineties, the recession hit hard. The arrival of the Internet only exacerbated the problem.

Cordesse changed his approach radically during a reporting assignment in Kabul in 1995. He took the shots he was expected to take, but, at the same time recorded sounds, changed viewpoints, and started to make films using his photographs. His approach has been evolving ever since. He revisits various genres (portraits, panoramic shots, landscapes), examining the responsibility of the photographic image and its imaginary potential. He reinvents lengths and distances, goes off-centre, imposes his own demands and choices, and puts words to his pictures. For him photography has become one tool he uses among so many others to bear witness to the complexity of the world. In the process, he has forged his own testimonial ethos. This exhibition proposes a retrospective of Alexis Cordesse’s work in the form of ten collections, some of which have never been shown in public.

Kabul, A Weary War

1995

In the war-torn Afghan capital, plagued by rival militias, Alexis Cordesse recorded sounds and took photographs, mixing action shots with more contemplative work. This marked the first time he stepped away from pure reportage to produce a series of short films.

Itsembatsemba

1996

L’Aveu

2004

Absences

2013

Over a period spanning eighteen years, Alexis Cordesse produced three series on the genocide of the Tutsi people in Rwanda. He was aware that photography was limited when it came to bearing witness to a tragedy so complex and so extreme that any attempt to record or represent it was impossible. Instead, he took the shortcomings of the medium into account and added archive material and numerous interviews to his photographic approach. In Itsembatsemba

, Alexis Cordesse photographed what happened after the genocide, bodies being exhumed, commemorations for the dead and survivors in psychiatric hospitals. The combination of his photographs with extracts from Radio-Télévision libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), the propaganda channel used by those perpetrating the genocide to spread hatred, adds another layer of meaning. The words and voices contaminate and complexify the visual representations of the horrors to remind us that any extermination, before becoming an act, is an idea, a word, born from a human mind.

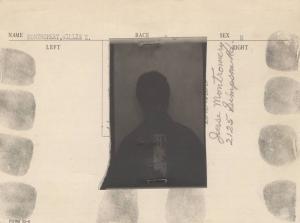

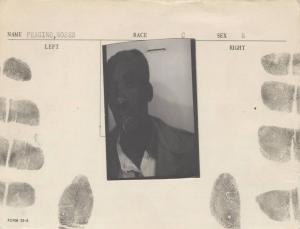

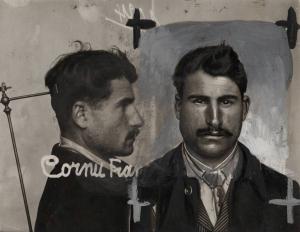

In L’Aveu

, Cordesse photographed the perpetrators of the genocide according to a strict protocol: dark backdrop, neutral lighting, frontal shot in colour. The portraits come with extracts from interviews he conducted with the subjects. For Cordesse, genocide is an inhuman crime, committed by humans. He considers the perpetrators of the genocide to be “in our likeness” to use Georges Bataille’s expression; his portraits attempt to reveal the ambivalence and complexity of these people without making any moral judgements. He avoids all dramatic effects, working at the same height as the subjects, varying his framing and continually asking himself questions, asking us questions: from what distance do we look at these men and women?

The final part of the trilogy is a series made nineteen years after the fact. Playing with the old colonial cliché that referred to Rwanda as “a paradise with a thousand hills”, the Rwandan landscapes in Absences

are devoid of any human presence, instead revealing a luxuriant view of nature that invites contemplation. No trace remains of the events, except for a complete list of the victims on a memorial wall, a commemoration scene shot from afar and the voice of three women, two survivors and one “just”. Faceless witnesses, who tell us what happened to them in this apparently tranquil place.

Borderlines

2009-2011

Borderlines

, sees Cordesse revisiting a photography classic – the panoramic shot – using contemporary digital techniques. He examines the question of borders in the Holy Land, a place that is saturated with media stereotypes where there is always something happening. His project is two-fold, to bear witness to the fragmentation of a territory where separation is the watchword, and to use photographs in composite form to create depictions that blur the lines between description and fiction.

Talashi

2018-2020

Talashi

is a “appropriated” piece that has never been shown in public before, made up of the personal photographs of Syrian exiles that Cordesse met in Europe and in Turkey, and who agreed to hand them over to him. The piece blends the intimately personal and the historical. The everyday images chosen by Cordesse are all familiar to us. Removed from the current affairs and news stories that surround them, they allow us to imagine and empathise with the lives of these ordinary people, that have been turned upside down by extraordinary events.

Olympus

2015-2016

A Greek friend once told him “You should climb Mount Olympus”. Cordesse was in Greece for a job on the political landscape in a region that the weather suddenly made inaccessible. Instead, he climbed up the legendary domain of the Gods, that he never even knew existed geographically until that very moment. Climbing the mount takes physical effort and awakens the senses. The physical, not mystical ascension, puts the climber into a particular mental state. He undertook the climb six times, and each time had the same feeling of connecting with the world.Cordesse later associated the exceptional images that came

out of this unexpected experience with snapshots of his everyday life. Olympus

is a meditative, pensive piece, a complex ensemble with no documentary logic that creates a secret echo. In addition to his work outside of press photography, Alexis Cordesse is also a portrait taker of note. The exhibition will present two iconic series that show his approach to the portrait, giving visitors an opportunity to discover work that has never been seen. In these three ensembles, the timeframes are long, the work happens year after year, and the repetition creates a form of trust and complicity with its subjects.

La Bruja

1999-2001

Cordesse retired to Cuba after ten years of working in conflict zones. When living in Havana, during a trip up the island’s east coast, he discovered the village of La Bruja. Located at the foot of the Sierra Maestra, it is a particularly remote place and it can take days to get there sometimes. He stayed with Lela, who lived in the only solid house in the village. To thank her, he took her portrait with a Polaroid. The first shot led to others. The village inhabitants came, one by one, dressed in their most beautiful clothing. Alexis Cordesse went back to the village regularly over three years and became the village’s official photographer.

La Piscine

2003

Summer 2003, the aquatic centre in Châtillon-Malakoff in the southern suburbs of Paris, became an

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Curated by

Anne-Marie Filaire

and Sylvain Besson,

musée Nicéphore Niépce

All of the prints for the exhibition were produced in the laboratory at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce on Canson Infinity Baryta Prestige 340g paper.

The museum would like to thank: Canson and La société des Amis du musée Nicéphore Niépce.

Anne-Marie Filaire is not a war reporter who files dispatches from the world’s hotspots. She observes the effects of war, the changes it leads to, the wounds that remain. These are disasters that have cooled off, that cannot be fixed, they must be absorbed and only time can make them fade, but not disappear. Her recent work in Paris and its surrounding regions, happily not exactly at war, most probably needs to be approached from that angle.

Jean-Paul Robert,

D’Architectures, Nov. 2020

Anne-Marie Filaire was 25 years old when she became printer Yvon Le Marlec’s assistant in Paris, a job she held from 1987 to 1991. After getting her technician’s diploma from the Crear laboratory, she immediately went into art printing. Print photography was booming and Le Marlec was one of a select group of well-known printers that every big-name photographer wanted to work with: Dirk Braeckman, Bernard Plossu, Bettina Rheims, Patrick Zachmann… Just like Philippe Salaün or Claudine Sudre, Le Marlec knew how to get the best out of their negatives.

In 1989, Le Marlec had big plans. It had been ten years since he left his job as printer at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce and set up shop in the Rue de Charonne. His ambition was to contribute to the history of photography by inventing a new process. In tandem with the chemist Christophe Bart, they developed a process to develop photographs using daylight. In order to publicise their invention, Le Marlec organised a spectacular show set to music specially composed for the occasion for the closing night of the Rencontres d’Arles. In an old theatre, lit by projectors, he revealed a latent photographic fresco, a giant photomontage (27 panels that measured 1.10 x 1.10m) of extracts from photographic masterworks and portraits of photographers, from Lewis Carroll to Helmut Newton, Bruno Barbey to Edward Weston… The evening was a triumph for Le Marlec who appeared on stage dressed all in white, catching the light, like a guru.

Anne-Marie Filaire worked to assist Yvon Le Marlec during the months-long preparation and manufacturing of the photomontage. She immortalised each instant, revealing the daily goings on of a photographic laboratory, showing every detail until the big reveal on July 8th 1989… Photography was grateful.

The dark room

I arrived in Paris in 1987, and moved into a small top-floor apartment, at 81 rue de Maubeuge in the 10th.

In those days, being a photographer was not really a job. One started out assisting other photographers, in fashion or advertising [I was an intern on a shoot for an ad by Gerhard Vormwald with the famous slogan ‘Ma chemise pour une bière

’ (My shirt for a beer)], for magazines, or as a laboratory technician. There were a lot of labs in Paris, and print photography was big so I chose to go into printing. But I didn’t want to do any old thing, I didn’t want to work in a big lab, I wanted to do art prints.

A well-known printer, Yvon Le Marlec, had just set up shop and was considered to be the best photographic printer in Paris. I had heard about him as I was finishing my photography course.

I was ambitious and determined so I just went to see him with my landscapes of the Auvergne that I had taken and printed myself. I told him I wanted to work with him and he hired me on the spot. So that’s how I started working straight away in Paris, just after I qualified as a lab technician at the Crear. I started working immediately at 5 rue de Charonne with Yvon. To begin with, I did the baths and retouching, until the lab got another enlarger and I started printing. I stayed there until February 1991.

The first photos I ever touched were by Pierre de Fenoyl. At the time, Yvon was working on “Chronophotographies

”, a book published for the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne and Charles-Henri Favrod.

Pierre de Fenoyl had just died and I discovered what an impact his death had in the photography world. That was my first physical encounter with a piece. Touching the material, handwashing soaking prints for hours, feeling the paper as it dried, pressing it, letting it stretch, retouching the photos with a brush.

The work I did for those four years was difficult and painstaking. Working in a lab is not easy,

but I was feeding myself intellectually. I met all of the big-name photographers of the day Denis Roche, Bernard Plossu, Antoine Legrand, Bettina Rheims, Xavier Lambours, Paolo Nozolino, Patrick Zachmann, Gladys, Marc Le Méné, Marie-Paule Nègre, Pascal Dolémieux, Agnès Bonnot, Thierry Girard, Ève Morcrette, Claude Dityvon, Jean-Michel Réverdot, Gérard Rondeau, Alain Turpault, Hervé Rabot, Pierre- Olivier Deschamp, Gilles Favier, Claude Bricage, Paul Facchetti… The portraits of Edouard Baldus, the work of Jacques-Henri Lartigue whose I make the preparatory prints for upcoming exhibitions and publications, François Hers and the DATAR Mission photographs. But also those of the magazine Actuel, Claudine Maugendre, Jean-Luc Monterosso, Dominique Gaessler, Pierre Devin, and Claude Gassian, who was on the fringe of the art world at the time. I chose to work with him and I printed the work for the first albums he did for Jean-Jacques Goldman, Renaud, and then for Rock images. The Niépce prize-winners also came from the lab on the rue de Charonne. We also produced the work of foreign photographers who worked all over the world and the developer revealed images by Gabriele Basilico, Sebastiao Salgado, Josef Koudelka, Jeanloup Sieff, Helmut Newton,Robert Mapplethorpe, Marc Trivier…

When André Kertész’archive arrived in Paris in 1987, I was lucky, or privileged enough to look at each of his contact sheets, one by one, to discover part of his work and life. It was, and still is, one of the most moving experiences of photography I have ever had. I have Isabelle Jammes to thank for it, who was working with Pierre Borhan at the time on the publication of Kertész’ “Ma France

”, a book and exhibition for which Yvon Le Marlec produced the prints for the Mission du patrimoine photographique.

I learned everything I know about light and photographic material during those four years. Yvon taught me one really important thing, to know when to stop. I think that is the biggest lesson from my early working life. A photographic print is made from living matter and we are always trying to get the best print possible. We play with chemicals, we look for nuances, depth, light. It can go on forever, and I learned that over the years. At the start I would arrive early, I would prepare the developer according to whatever prints Yvon had to do during the day, varying levels of contrast, according to the paper. I became an expert in dosing hydroquinone, phenidone, sulphite… and I would leave late, having washed, spun and dried all of the prints during the day, to run off to pick my son up from school.

The first exhibition I printed was Lartigue’s “Les femmes

aux cigarette

s”, from glass platenegatives, where one of the faces that appeared was Josephine Baker’s. An entire pantheon opened out in front of me in the dark. My intellect and imagination were nourished by world events and the big changes of the time such as the demonstrations and repression at Tiananmen Square in Beijing. I discovered people from the world of art, literature, the world that I knew from what I was reading, came to life in the floating pictures I handled every day.

At lunchtime, I would go to dance classes at the Café de la Gare. Between two washes, I would go to see films at the Bastille cinema, I remember seeing the Rossellini season from beginning to end. The lab was located at the back of a large courtyard that housed artisans and upholsterers, near Bastille on the corner of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. I used to sometimes visit the offices of the Cahiers du Cinéma

that were on the Faubourg. At that time, when I was printing other peoples’ work, I was also taking photos, every day with an autofocus L35 Nikon. This exhibition at the Musée Nicéphore Niépce reconstitutes this photographic journal from the busy period when we were working on the fresco for the Rencontres Internationales de la photographie in 1989.

Since 2011, I have been teaching photography at Sciences Po, and I lecture on this period of the history of photography, that I took part in, and that I am still writing today. Photographers from the eighties, were very much part of a tradition, Arago’s announcement of the existence of photography was only 150 years old, we were inspired by the Americans, it was a time of big exhibitions, and when photographybecame part of contemporary art.

Anne-Marie Filaire,

Paris, June 2021

Biography

For over twenty years, Anne-Marie Filaire has been exploring landscapes on regular trips to faraway places, mainly to the Middle-East and Asia. The notion of time is important to her work. Her time frame is frozen, the space of trauma, the blindness of conflict, or even repetition, that she depicts in an extremely constructed and structured fashion She photographs zones where conflict has happened, is happening or is about to happen. Motivated by intimate sparks, far from her family and her home, Anne-Marie Filaire looks for “beauty in light and violence” 1, questioning notions of borders and enclosure, inside territories where history and men have left their trace. While humans are practically absent in her photographs, the stigmata of their passage are omnipresent and the unease is, at times, palpable.

Anne-Marie Filaire’s landscapes are brave and poetic. She never gives in to simplicity, her own stance and subjectivity are key as she explores dangerous regions where it can be risky to be a photographer. By regularly going back to the same places, Anne-Marie Filaire composes an archaeology of these territories. Her process is identical, whether she is photographing landscapes in Auvergne for ten years for the Mission de l’Observatoire Photographique du Paysage or the installation of a wall between Israel and the Palestinian territories: repeated viewpoints, a fascination for the horizon, very structured framing. Her still, silent landscapes bear witness to the passage of time. The true subject of her work turns out to be time itself: photographic layer after photographic layer, the accumulation documents, objectivates but above all, creates a body of work.

Anne-Marie Filaire was born in 1961 in Chamalières (63), and was photograph printer Yvon Le Marlec’s assistant in Paris from 1987 to 1991. Her first, seminal series was created between 1994 and 1996, dedicated to volcanic landscapes in the Puy-de-Dôme and the Cantal (that led to her first personal exhibition at the Musée d’Art et d’Archéologie in Aurillac) set her up as a landscape photographer. In 1999, she began travelling through the Middle- East and Asia, while in France she worked with the Mission de l’Observatoire Photographique National du Paysage. Her work then shifted toward the notion of environments that she depicted through series on doors and bedrooms. She now teaches photography at the Paris Institut d’Études Politiques. Her work has been shown in many exhibitions in France and abroad. The Mucem, in Marseille, held a solo exhibition in 2017 the highlight of which was Zone de sécurité temporaire

(Textuel / Mucem, 2017).

Anne-Marie Filaire continued her exploration through the excavations of the Grand Paris. A number of exhibitions planned for 2022 will showcase this work. In 2020, she published Terres,

sols profonds du Grand Paris

with Éditions Dominique Carré / La Découverte, en 2020.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

AZIMUT

A photographic journey

with the Tendance Floue collective

10.24.2020 ... 01.24.2021

Opening Friday Oct. 23 th 7 pm

AZIMUT

[from the Arab (as-)simt, the path

],

March – Octobre 2017

A photographic journey.

In France.

French photography has a new found sense of freedom. The Tendance Floue photographer’s collective grew tired of the constraints of commissioned work, and were eager to get back the feeling of independence that defined the movement’s origins, so they decided to go on a road-trip. The idea was to travel around in a relay, exploring the countryside, wandering aimlessly through the cities and towns. Their only requirement was to move forward a little every day and to document their impressions of the road in words and images, before passing the baton on to another photographer. The idea was not to take a break, but to open a window on the world.

At the time, the Tendance Floue collective was about 25 years old, a quarter of a century in other words. That crucial age where freedom meets maturity. Everything is possible at that age. It is the time we break free to travel the world, when we define and appropriate a place, alone or with friends.

The members of the collective invited other photographers to share their road-trip experience. With the new-found freedom of Azimut, the collective came into its own. One echoed the other.

The unprecedented six-month relay-journey involved fifteen members of the collective and sixteen guest photographers. Travelling without a specific aim is what defines any adventure. While the path taken was incidental and the destination unimportant, documenting the Azimut was the one rule everyone had to follow. A Moleskine notebook was handed from traveller to traveller like a relay baton, forming a common thread between the photographers. Travelling meant knowing when to stop, to be able to write, comment, express their fears, share their encounters and, at times, log their dreams. The story of the journey is told in both photographs and words. Social media kept a daily track of their activities as each day, a photograph was posted to an Instagram account with comments from the photographer. The project was also recorded in self-published notebooks, almost in real time, anchoring it very much in its time.

The French landscape has already been extensively documented photographically, from the Mission héliographique that began in 1851, to DATAR in 1984 to France Territoire Liquide in 2017. Tendance Floue reinvented the genre and took it outside the box, without waiting for the next institutional campaign. Everyone was free to choose their own path, literally and figuratively; they were even free to get lost, all the better to trace an instinctive cartography of the landscapes they travelled through. Azimut gives us an unfettered look of a territory in the concrete sense of the term, while also exploring the personal territories of the artists. It forms a collective trail that makes room for each individual to express themselves.

With:

Bertrand Meunier,

Grégoire Eloy,

Gilles Coulon,

Meyer,

Antoine Bruy,

Pascal Aimar,

Alain Willaume,

Patrick Tourneboeuf,

Mat Jacob,

Kourtney Roy,

Pascal Dolémieux,

Michel Bousquet,

Julien Magre,

Stéphane Lavoué,

Léa Habourdin,

Fred Stucin,

Marine Lanier,

Clémentine Schneidermann,

Mouna Saboni,

Guillaume Chauvin,

Yann Merlin,

Gabrielle Duplantier,

Olivier Culmann,

Bertrand Desprez,

Julien Mignot,

Thierry Ardouin,

Yohanne Lamoulère,

Marion Poussier,

Denis Bourges,

Flore-Aël Surun,

Laure Flammarion

and Nour Sabbagh

Curated by:

Anne-Céline Borey, Sylvain Besson, musée Nicéphore Niépce

All of the prints in the exhibition were printed in the Musée Nicéphore Niépce’s laboratory on Canson paper Imaging, Photo Mat Paper 180 g and Infinity, Rag Photographique 310 g.

The museum would like to thank:

Canson, The Société des Amis du musée Nicéphore Niépce, all the members of the Tendance Floue collective and their guests, in particular Clémentine Semeria, Grégoire Eloy, Bertrand Meunier and Fred Boucher.

Edition:

Azimut

Éditions Textuel

ISBN : 978-2-84597-821-8

17 x 23 cm

288 pages

35 €

Bertrand Meunier

I went down to the banks of the Seine to observe the retirees and their dogs. I thought about the soap opera “The Young and the restless”, and about my mother who I haven’t seen since the summer, about the little things in life, in mine, in yours, in the world. It was nice. Everything was calm. The barges were quiet.

Grégoire Eloy

I read as I walked along an endless straight line. A straight road can undermine any long-distance athlete. You just have to look ahead where the road meets the horizon and your legs will suddenly give way and you will be taken over by the immediate urgeto abandon the race.

Antoine Bruy

I take a photo of the couple alongside their bearskin. It’s awful. I go to bed with aching legs.

Meyer

I arrive in Vézelay, liquid and dissipated like the rain, a ghostly pilgrim. I give in to the urge to wander around the village for the last time. The journey is over. I’m ready to meet Antoine, it is his turn to take to the road now. I think about my friends Tendance Floue, about the others, about all those who have a taste for the urgent and the futile.

She says nothing.

I say nothing. We share the inexpressible.

She leaves.

In a few bewildering hours, I am in Paris.

Alain Willaume

The sun is fading. I set up camp beside a small lake and lie down for a long time, loosening my back, relaxing my shoulders, pushing back against the pain. I start to hear the fish murmuring, far, far away. As dusk settles, I can barely make out the hound of the Baskervilles through the tent opening [...] I am here, I recognise and I understand, I share what I am told. And everything is new again.

Mat Jacob

STRIKE! INSURRECTION!

— Communiqué zéro

31.05.2017 – 10:44

THE OUPAS STRUGGLE BEGAN ON THE PLATEAU DE MILLEVACHES, HOTSPOT OF RADICAL THINKING AND RESISTANCE OF ALL TYPES. FROM OUR REFUGE, OVERLOOKING A CLANDESTINE HILL WITH AN AMAZING VIEW, WE HEREBY ADDRESS THE AZIMUT COMMUNITY THROUGH COMMUNIQUÉS IN ORDER TO CALL FOR A STRIKE AND FOR INSURRECTION. WE, JOSÉ CHIDLOVSKY AND MAT JACOB, HEREBY DECLARE THE IMMEDIATE CESSATION OF THE AZIMUT JOURNEY. WE ARE IMMOBILE, WE HAVE STOPPED WALKING ALL THE BETTER TO TRAVEL. OR NOT. THE OUPAS STAND FOR ABSOLUTE FREEDOM, THE INVERSION OF THE OBVIOUS. WE ARE THE OUPAS.

Stéphane Lavoué

This countryside is dying, it convulses as it spits out its hatred for others, for strangers. These people feel abandoned. Their anger is misdirected.

Léa Habourdin

It is exciting to keep moving. I am tempted to go far, to go fast, to start counting the kilometres, to pat myself on the back. But I loaded up my bag of rocks and this eulogy to weight prevents any urge to travel, I will not go far, I will not go fast.

Fred Stucin

I’m sick of green, of rocks and hikers. That’s it, I’m heading for town. Tarmac, buildings, bars. Luckily for me, some guy painted the rocks green, the Cévennes’ answer to Basquiat. It’s ugly, and he did it all the way to the village. It did help me get as far as my guesthouse though. Fucking Azimut.

Clémentine Schneidermann

The sea is still far away. We are exhausted. We stop for the night at the Évasion camping site. I open my tent, wrinkled and dirty, unopened since my trip to Greenland a few weeks ago. The campsite is fun. People greet us, we’ve been spotted.

As night falls, I take photographs of a group of pre-teens hanging around near the pool table. “Miss, what paper do you work for?”, one boy asks. I ask him what paper he knows. “The Racing Post” he answers.

Guillaume Chauvin

I keep climbing. A bird brushes past me, as noisy as a kite. At times I have to crawl through the undergrowth, humming Azimut. Just then, Anastasia texts me to say Victor has taken his first steps. Time dances in a blur before my eyes.

Julien Mignot

Like I was saying, walking is not very well suited to photography. Well, not to mine in any case. It is too measured; the landscape keeps repeating itself.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Jean-François Bauret :

perceive, receive

February 14th

… May 17th

2020

Opening Thursday February 13th

at 7pm

Curator: Sylvain Besson, Musée Nicéphore Niépce

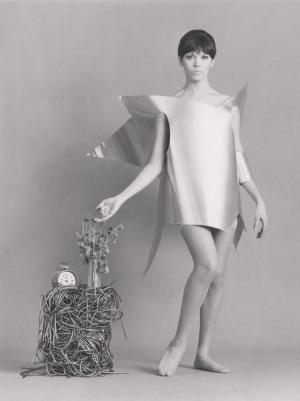

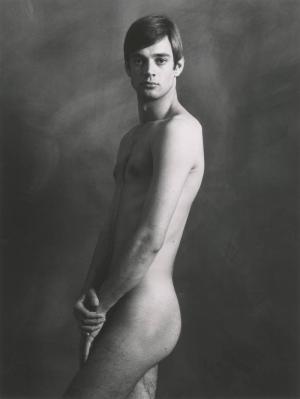

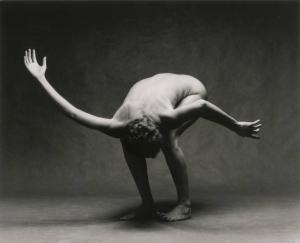

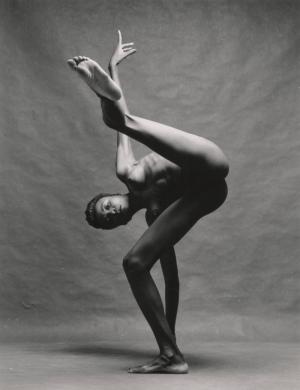

When Jean-François Bauret’s career began in the late fifties, anything was possible for a young, self-taught, enthusiastic, attractive photographer with plenty of connections. It was the time of the Trente Glorieuses, post-war reconstruction was ongoing, advertising was booming and sexual freedom was just around the corner. Jean-François Bauret spearheaded photography in advertising and, in his own way, can be said to represent half a century of the short history of photography.

The musée Nicéphore Niépce acquired the Jean-François Bauret archive in 2016. Three years of inventories, digitisation and research by the museum’s team have made things very clear: Jean-François Bauret was a prolific and transgressive advertising and fashion photographer; he was also an artist and portraitist truly of his time.

The size and diversity of the archive is rare, and it shows the work a photographer who cannot be reduced to two flashy scandals and a few series. This exhibition, entitled “Jean-François Bauret: Perceive, receive” proposes a retrospective of the artist’s career in almost four-hundred and fifty photographs. For the first time ever, the photographs, selected from the four-hundred thousand in the archive, will include both paid commissions and artistic pieces by the photographer.

Scandalous? Subversive? Modern? Trailblazing? Iconoclastic? Self-indulgent?

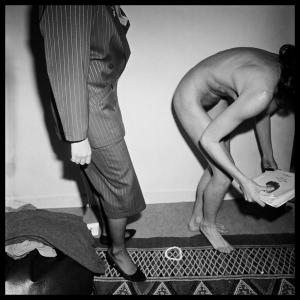

Showing Jean-François Bauret’s work is a challenge today as, while he was a photographer very much of his time, it would be almost inconceivable to show some of his nudes, were they to be shot today, even though they are what made his name between 1970 and 2000.

Jean-François Bauret, like so many photographers, was first and foremost a craftsman. When the medium was undergoing a transformation, he covered almost every genre. He managed to combine professional paid work with his artistic output, but there was such an emphasis on the latter that his commissioned work was often forgotten about. However, we must point out that his personal work makes up a tiny part of his archive.

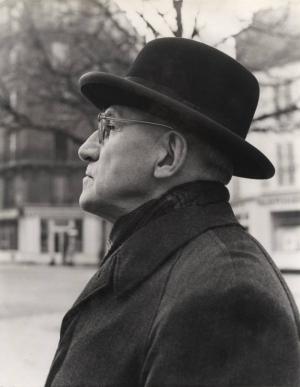

His early work included portraits of artists such as Bram van Velde, Pierre Alechinsky and André Lanskoy. The painters, sculptors and musicians photographed were all under the patronage of his father, Jean Bauret, an industrialist, patron and collector from the Lorraine region. These intimate, edgy portraits, were often taken in the artists’ workshops and his attentive eye and narrative sense as well as his talent for lighting gave these portraits a timeless feel.

However, Bauret’s career really took off when he met the interior designer and stylist Andrée Putman. She was responsible for his early commissions for the magazine L’Oeil and the Prisunic stores. Thanks to his name and his network, the advertising jobs came flooding in. With the help of his wife, the painter and collector, Claude Bauret-Allard, who acted as both his assistant and model, Jean-François Bauret was at the forefront of the genre’s renaissance. His compositions, inspired by Claude, were a hit. The body (often Claude’s), either blurred or against the light, was omnipresent in his early work. The poetry of the compositions took the chill off the articles being advertised which included everything from beauty products to sheets to spaghetti…

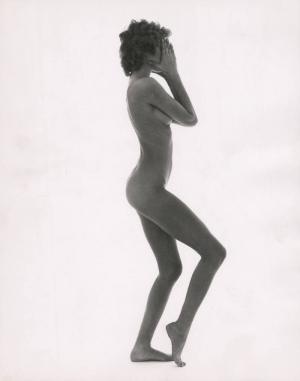

Bauret soon established himself as a photographer but two campaigns for Publicis had a huge impact and were to raise his profile suddenly. Bauret insisted on using a naked man for the 1966-1967 campaign for Sélimaille, a men’s underwear label. In the Spring of 1970, he shot a naked pregnant woman and child for Materna. Feedback to the advertisements was as heated as the audacity of his approach, as never before had any brand used an entirely naked man or pregnant woman in a campaign. The reactions to both campaigns were negative and violent. They brought in a sea change in advertising in the sixties, showing the growing importance of photography, and heralding a new way to use the body to sell products. Bauret soon made a name for himself as a subversive and provocative photographer.

Both campaigns were based around a nude portrait, which was to become a veritable obsession for Jean-François Bauret. His shots were like an inventory of the body, full-frontal, taken in the studio on a neutral background and with subtle lighting. “Beauty” didn’t come into it, he revealed bodies with no artifice, as he felt this was the only way to get a to the subject psychologically.

Jean-François Bauret added to the renaissance of the portrait and the photographic

nude, far from the academic poses of the 19th

century, the daring angles of the New Vision and the ambiguous sensuality of some of his contemporaries.

As early as the seventies, Bauret began to show and gain recognition for his artistic work, but he never abandoned the bread and butter side of things. He shared his work through Photothèque , maintained close links with big magazines such as Jour de France, Enfant Magazine, Télérama, Actuel and Jardin des Modes and with brands like New Baby and Air France and remained determined to stick with the less artistically rewarding but highly lucrative aspect of his job.

Baudret was truly a significant photographer. He showed his work frequently with 62 solo exhibitions and 57 collective ones between 1956 and 2008. Baudret also shared his knowledge and experience with amateur photographers through courses and workshops, holding a total of 41 between 1982 and 2005 and he worked tirelessly to raise awareness for the medium and keep it in the public eye, notably setting up the website photographie.com in 1996.

He was a man of few words who turned into a chatterbox once he got into the studio, and he left behind him many images but wrote little. What was Jean-François Bauret looking for? And was he even looking for something? Was photography nothing more than a job for him, or was it a pretext? The sheer profusion of his work leaves the unfinished feeling of his attempts to grasp something, his inability to capture the nudity that was the last path to abandonment.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

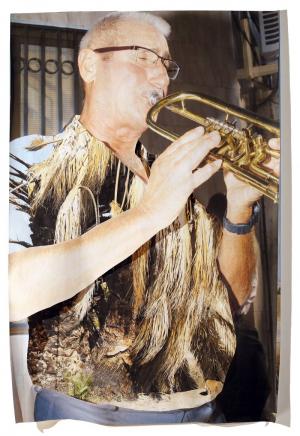

Ricardo Cases,

Estudio elemental del Levante

06.15 ... 09.22.2019

Ricardo Cases is a Spanish photographer. He was born in 1971 in Orihuela in the Alicante province on the Mediterranean coast. He started out as a reporter and in the 2000s became a leading light in the rebirth of Spanish contemporary photography, in particular as part of the Blank Paper collective. His 2011 book Paloma al aire, thrust him onto the international stage. It chronicles the activities of pigeon fanciers in the Valencia region of Spain taking part in an unusual local race where the male birds are painted in bright colours.

The ”Estudio elemental del Levante” (An Elemental study of the Levante) was his first solo show. It took place in Madrid in July 2018, and was a retrospective of five series the photographer did in the Levante – the Spanish Mediterranean coast – over a period of eight years. Ricardo Cases takes an interest in his environment but his work is not reduced to its documentary function, to the recorded fact. Instead, he explores all of the photograph’s semantic possibilities. His work features blinding lights, explosive colours, damaged objects, and decadent characters, revealing the visual singularity of this “undisciplined, fascinating and hallucinogenic country.”

The first impression of Ricardo Cases’ photographs is fun, but they allow the viewer to get beyond stereotypes, to get to a deeper level, that highlights the shortcomings of the region. They may be set in a specific geographical perimeter, but these photographs have a universal reach in terms of the way territories change, their feeling of nostalgia and the way they respect local treasures and traditions.

From his first works, Ricardo Cases’ particular creation has been filled with radicalism, vitality and humour, and it is imbued with an anthropological and ultimately tender view of his subjects, which are always involuntary representatives of the Spanish nature.

This intuitive photographer honed his process until he managed to be several steps ahead of himself and capture truths that it would then take him months to decipher. His latest work flies higher, with a more sophisticated language that takes a much higher artistic risk, but always with a playful background that still inspires our capacity for wonder and conveys his enthusiasm for photography (and for life in a wider sense) seen as a game. In all these years of work, his critical and yet sincere fascination with the Iberian spirit has created, in the life-sized laboratory of the orchards of Valencia, a complex repertoire that contains the keys of Spain, but especially the keys of the Spanish nature.

After receiving the Culture Award of the Community of Madrid in 2017, this is the first opportunity to contemplate such a wide and coherent sample of his work. The collection of series including Paloma al aire [Pigeons in Flight], Podría haberse evitado [It Could Have Been Avoided], Estudio elemental del Levante [An Elemental Study of the Levante], Sol [Sun] and El porqué de las naranjas [The Reason for Oranges] constitutes a powerful symbolic corpus that gives shape to the universe of Levante as

a colourful, anarchic, wild and confusing place. Welcome to this eerie Wonderland.

Paloma al aire

2011

These are the rules of the game: a female pigeon is released and several dozens