Photography: a technical, aesthetic and social object

The ambition of the musée Nicéphore Niépce is to explain the basics of photography from its invention by Niépce up to today’s digital imagery. Its collections bring together almost three million photographs and objects that provide the possibility of a constantly renewed experience visit after visit. The use of interactive terminals and increasingly sophisticated technology provides a deeper understanding of the photographic world.

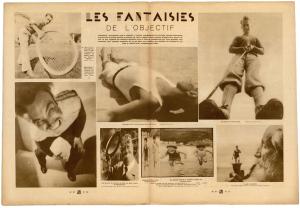

The museum is planned as an initiation to the broad principles of photography. Professional prints are displayed side by side with amateur efforts. The illustrated press has an important place as an essential support to the worldwide spread of the medium.

The collection’s central room: the Discovery room, with the world’s first camera used by Nicéphore Niépce, the inventor to whom a room of the museum is dedicated.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

The invention of photography

Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833) was an unlucky inventor whose merits were not appreciated until well after his death. He was associated with Louis Daguerre (1787-1851), but died before he saw the fruit of their shared work gain the recognition it deserved. In 1839, Arago presented photography to the world as solely the invention of Daguerre.

The museum displays different objects from Niépce’s laboratory, in particular the heliographs (from the Greek helios meaning sun and graphein meaning to write). These are one-off pieces made by Niépce himself, and are considered to be the first photographs (the term photography only appeared in 1839 in a speech given by François Arago at the Académie des sciences). To record a heliographic image, Niépce covered a metal plate with Bitumen of Judea dissolved in lavender essence. The plate then became photo sensitive. Once it had dried, it was placed in a camera obscura , and exposed to the light for many hours. The image captured was latent; to make it appear, the plate had to be immersed in a bath that dissolved the parts of the bitumen that were less exposed (the bitumen that was exposed to strong light hardened and didn’t dissolve).

The oldest heliography recorded dates from 1826 and is today part of the collections of the University of Texas in Austin. It is entitled Le Point de vue du Gras , and represents a landscape not far from Chalon sur Saône. The image is fixed on a tin plate with a mirrored aspect that makes it hard to see. This one-off piece is reproduced at the musée Niépce thanks to digital technology using a flat screen that the visitor can handle themselves. Current technology helps us to better understand Niépce’s initial process through film.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

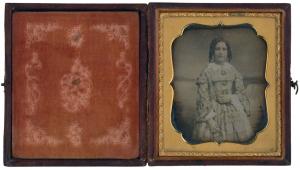

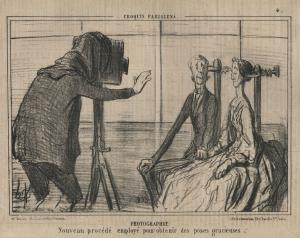

The museum gives over a room to Niépce’s famous contemporary who was also his partner, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851). The procedure developed by the latter, the daguerreotype (1839), was a great commercial success up until the 1860s. It used a brass plate covered with a layer of silver on which the image was fixed. It was most often used for portraits or architecture photographs as the daguerreotype produced an image of great precision. It has often been criticised for its coldness, sometimes compensated for with colour retouching. The images were unique, could not be copied and incredibly fragile, so most often protected in special cases.

Research at the beginning of the 19th century to fix and reproduce mechanical images was obviously not confined to France. In 1835, the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) invented the first ever negative on paper (calotype) which permitted the endless reproduction of a positive image. The museum possesses one of the rare examples of Talbot’s work, The Pencil of Nature (1844) where the writer explains the advantages of his procedure in photographing landscapes and still life (the exposure time needed was quite long at the time). The collections also contain hundreds of calotypes that are exhibited intermittently due to their fragile nature.

The calotype gave us the negative-positive duo that would characterise photography up until the digital era.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

The silver revolution

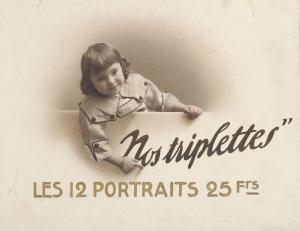

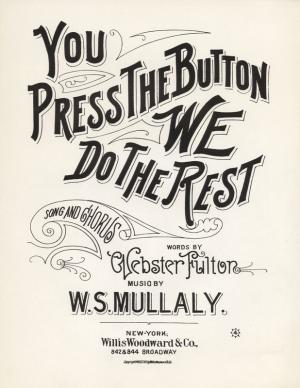

As time went on, the negative changed, materials went from paper to glass, then to flexible film. Emulsions were perfected, enabling shots to be taken faster, cameras easier to use and as such, photography became more « democratic ». A room half way through the visit provides a summary of these changes and underlines the importance of the emergence of the gelatine-bromide silver emulsion in the 1880s. This emulsion was extremely light-sensitive and enabled shots to be taken in a fraction of a second. These instants captured a step being taken, a bird taking off, a sportsman jumping. Now that long posing times were no longer necessary, portraits were less frozen and shots began to look more spontaneous. The museum exhibits a number of images illustrating the procedure as well as the different types of negatives that were on the market at the end of the 19th century. The first hand-held cameras are also on show, like the

Kodak Pocket, which was so easy to use that it was largely responsible for the boom on amateur photography.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

In 1907, the Lumière brothers marketed autochrome plates that enabled colours to be captured in one shot. The basis remained the same but, instead of using three separate filters, they combined them to form a constellation of little transparent green, orange and violet dots fixed directly on the photographic plate. These unique and fragile images had to be looked at as slides. The freshness of the colours is still surprising today.

It should be pointed out that the principle of decomposing light using coloured filters and recomposing the colours in the printing process is still the mainstay of photography in the digital age. A digital captor has red, green and blue filters. The addition of these three colours in equal doses reconstitutes white light.

In addition, our current printers recompose the colour subject using inks of three complementary colours to red, green, blue: cyan, magenta and yellow. The addition of all three in equal doses reconstitutes black.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Relief photography

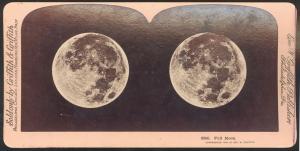

Constantly searching for the most faithful transcription of reality possible, photography took an early interest in the three-dimensional. A number of processes were developed that relied on the physiological capacity of binocular vision to give the impression of relief.

The museum’s collections have a number of characteristic examples of the different techniques of relief. Among them, lined and lenticular networks enabled three dimensions to be perceived without using a machine or glasses. The multiple views necessary to recreate the effect of depth were built behind a network of opaque and transparent lines or lenses. The network was part of the image as such. These techniques were experimented and developed in France by Eugène Estanave as early as 1904, and then by Maurice Bonnet who marketed them in 1937 through his company La Relièphographie . Since their invention, these spectacular images have been frequently used for fun or for advertising.

One room in the museum is given over more particularly to stereoscopy. Thanks to the didactic qualities of new image technologies of the image, hundreds of stereoscopic view can be seen in spectacular 3D.

The stereoscopic photographs on glass or cardboard which were in vogue since the Second Empire and up until the 1930s, were originally seen individually through an optical instrument (the stereoscope) that reproduced the effect of depth and relief of the images. The museum proposes an interactive installation that lets visitors wearing polarising glasses, choose the themes they wish to explore among the particularly rich collection: the First World War, family photographs, Brittany, the world in colour, Japan, etc. Near the projector there is a display case that shows different models of stereoscopes and original shots. Finally, a 3D film takes a “verascope” apart (the camera used for stereoscopic shots dating from 1893) and enables the visitor to enter into the machine to get a better understanding of how it worked.

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français

Contemporary work and temporary exhibitions

The museum is not limited to just a historical relationship with the medium. Contemporary photography, whether it is art photography or reportage, also occupies an essential place in the museum. A complete room is given over to it where the collections, like the rest of the visit, are regularly changed.

For many years, the museum has supported contemporary photographers, while concentrating in-depth on the work of certain artists. So it holds hundreds of thousands of negatives and slides by Peter Knapp, a representative collection of work by Patrick Tosani, and important ensemble of work by the reporter Stanley Greene…

The Centre national des arts plastiques recently presented the museum with 89 works by French photographers such as Sophie Riestelhueber, Jean Le Gac, Patrick Faigenbaum, Jean-Marc Bustamante, Jean-Louis Garnell, Eric Rondepierre, Sophie Calle…

The attention given to contemporary photography is all the more important given that the museum has a digital photography laboratory adapted to the production of artists in residence or those supported by the museum.

The programming of the temporary exhibitions (six per year) also reflects this taste for current creations (Yuki Onodera, Mathieu Bernard-Reymond, Mathieu Pernot, Raphaël Dallaporta, Elina Brotherus…), as well as for the « older » greats (Robert Doisneau, Izis, Edourard Boubat…) and more specific themes (family albums, war images, street photography…).

28, Quai des Messageries

71100 Chalon-sur-Saône

phone / + 33 (0)3 85 48 41 98

e-mail / contact@museeniepce.com

Classic website / Français